Adrijana Turajlic

Art Historian and Curator

Museums have no borders,

they have a network

September 30, 2024

Keywords: street art, street art museum.

To reflect on this subject, I examine two very different approaches, those of The Street Art Museum Amsterdam (SAMA) and the Urban Nation Museum in Berlin, two institutions that focus on street art and its preservation.

From ‘graffiti’ to ‘street art’

Different researchers date the origins of street art in different eras; I would argue that street art began developing in the second half of 20th century − more specifically in the 60s and 70s −, along hip-hop culture in New York. At the time, hip-hop culture was a product of the ghettos, allowing marginalised minorities to express their voices. One of its main aims was to stop violence and give the youth a different form of expression (Chang 2007). The four main elements of hip-hop culture – DJing, MCing, b-boying, and graffiti (Light & Tate 2019) – eventually split and developed separately.

The evolution of graffiti gave rise to what we now call street art. Street art is an umbrella term that incorporates various types of art that one can find in the streets. The best-known techniques used by artists are: graffiti (usually done only with spray or airbrush), sticker art (art produced beforehand in a studio and later glued to walls), stencil art (artist produces at least a few cutouts in order to spray over them to create the artwork), and murals (the artwork is painted over a large surface). Nevertheless, many different innovations in street art are hard to classify.

A reflection on street art institutionalisation

Although street art is still mainly practised illegally, it gradually gained legitimacy and found its way into museums. The most common question that arose (and is still being asked) was then the following: should street art, which is supposed to be out in the streets, contemporary and interchangeable, now find itself ‘locked up’ in museums and galleries?

The street was indeed meant to be both the gallery and the museum. Furthermore, street art was also in public spaces to create dialogue: it challenged the rules of society because of its illegality, and also contributed to shape diverse discourses, especially those related to political or societal issues.

If we go back to the fact that street art was a voice of marginalised communities, by entering institutions that have rules and have been seen as places of privilege, but also oppression, doesn’t street art lose its very own original and free voice? Yet, by entering such institutions, street art gains first and foremost, legality, and a way of being seen by and presented to an audience. By being recognised by these institutions, street artists also get a chance to gain recognition for their work, and possibly make a career.

Although street art might be losing its very nature and intent, it is also gaining a lot. Many art forms or styles that challenged the very idea of art or a museum, are now part of some of the most famous collections in the world, taking their place in art history.

The Street Art Museum Amsterdam (SAMA)

The Street Art Museum Amsterdam is an ecomuseum that has a strong relationship with its neighborhood, Nieuw West. Most of the museum’s 300 or so artworks are spread around the district, which means that visiting the ‘museum’ offers an opportunity to learn a lot about its surroundings.

Figs. 1 and 2. The SAMA museum building and its surroundings (artwork: Tulips, by Orticanoodles). © Adrijana Turajlic

The artworks that comprise the ‘museum’ are not taken away from the streets but remain out there, available to everyone. The museum doesn’t own any of the walls on which the works are displayed, except one small central building covered in street art, which mainly serves for administrative purposes. Most of the artworks in this collection have been commissioned or created by hosting various events. Sometimes, even the inhabitants of the area have been included when deciding on the content of these artworks. Therefore, even though SAMA ‘solved’ the problem of how to present street art in its natural environment, we can’t help but wonder if something commissioned can really be considered ‘street art’. Taking into account that the community in this area is very marginalised, and the area is considered to be a ghetto, we could say that this gives in some way a voice to the marginalised, however, the voices of the artists depend on others.

Yet, another issue – a practical one – arises: as stated before, the museum owns a very small building, and all of the other pieces are spread throughout the neighborhood. Therefore, the museum does not technically own any of the artworks. If one of these walls is torn down, the museum collection will lose one of its pieces, even if the documentation of its existence will remain. Hence, we can ask ourselves: Is SAMA preserving the concept and phenomenon of street art rather than the works in its neighborhood?

Figs. 3 and 4. Street art works in the district (Glory by PEZ and Danny Recel, and Tolerance by Alaniz). © Adrijana Turajlic

The Urban Nation Museum, Berlin

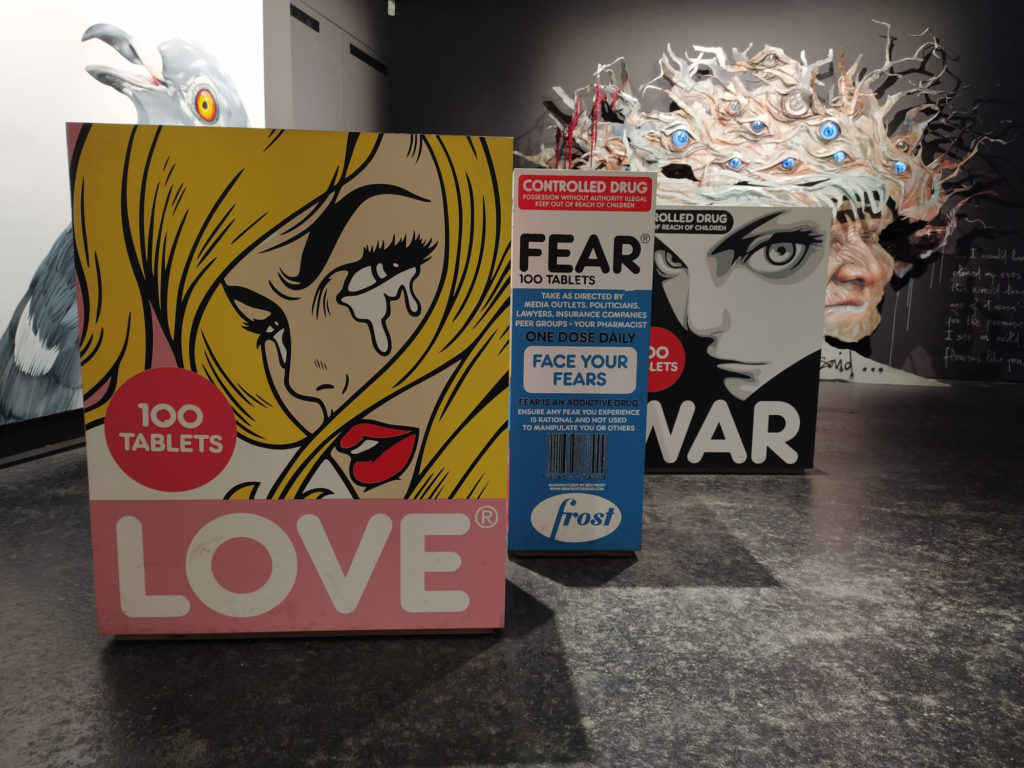

The Urban Nation Museum in Berlin is more conventional: it has a building and operates like a traditional museum. The majority of the collection is housed inside the museum building and the largest part of artworks is done in traditional forms (such as paintings, sculptures, videos, etc.) with a twist and in techniques typically used for street art. There are only a few ‘actual’ street art pieces located in the streets close to the building, which is, itself, covered in art.

Figs. 5 and 6. Museum interior and art installation/sculpture from the museum collection. © Adrijana Turajlic

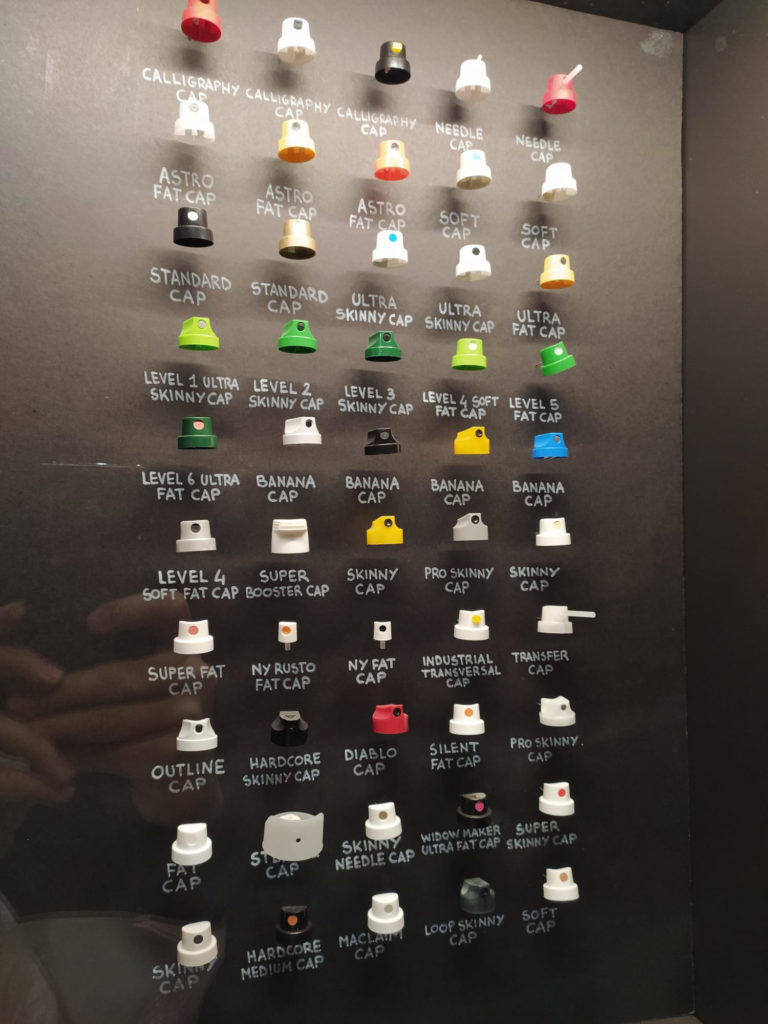

Fig. 7. Showcase of different spray caps. © Adrijana Turajlic

Even if most of the collection is not what we would consider street art pieces, this is not the first time that street art has been done in traditional art forms. It already happened, for example, in New York in 1973, when graffiti artists exhibited their artworks on canvases at Razor Gallery in SoHo (Blocal & Pope n.d.). Therefore, one can’t help but wonder if this is a way for institutions to bend and shape street art to their needs. If street art loses its spontaneity, message, and is no longer a thought provoking form of expression, nothing is left of it, but a style.

Conclusion

It could be argued that both SAMA and the Urban Nation Museum Berlin ‘only’ preserve and communicate the concept and the phenomenon of street art by safeguarding heritage. However, they also create bridges between the marginalised and the mainstream. Street art deserves to be researched and preserved in its own way, but the way in which it can be shown and preserved while respecting its nature, remains to be defined.

References: