Estelle Brunet

Art conservator and museologist

Museums have no borders,

they have a network

October 31, 2024

Key words: traffic in cultural goods, museums, restitution, Nepal, museum ethics

In recent years, a number of museums have been involved in international scandals linked to the possession of cultural goods believed to have been looted or illegally acquired. Through a number of activist associations, Nepal, a country rich in heritage, has requested the return of antiquities from several museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Art Institute of Chicago. A study of their institutional responses raises questions about museum ethics in the absence of a legal framework.

Legal and ethical framework for museums

The traffic of cultural goods is a lucrative criminal activity, estimated to generate several billion dollars a year (Potard, 2016). It relies in particular on the illegal export of historical objects from “source” countries to Western markets. The 1970 UNESCO Convention[1] and the 1995 UNIDROIT Convention[2] establish legal foundations for fighting such illicit traffic, but there are a number of challenges in applying them. First, every country oversees its own export controls, which makes it harder to manage goods crossing several borders. In addition, the UNESCO Convention is not retroactive, so it does not apply to goods exported before it entered into force, and the UNIDROIT Convention has not been universally adopted, only certain “source” countries have ratified it, and the statute of limitations has often passed for goods that were recovered later in time. Moreover, the application of these conventions may conflict with national laws protecting “good faith” purchasers. For these reasons, restitution procedures remain long and costly, and the absence of criminal sanctions under international law limits their effectiveness.

Fortunately, museum codes of ethics, although non-binding, have a strong influence on museum policies and practices for acquisition and management. They represent a moral commitment and reinforce the professionalism and accountability of the museum sector. ICOM[3], through its Code of Ethics for Museums, encourages museums to carry out due diligence (Frigo, 2016) to ensure that the objects they add to their collections come from legitimate sources.

Nepalese antiques and the American market

Religious objects play a central role in religious practices for 90% of the population in Nepal (Nepalese Culture and Religion, 2017). Although Nepal has escaped colonisation, its cultural heritage is still vulnerable. Its many antiquities have been poorly documented and protected, making them vulnerable to looting. The cultural link between the United States and Nepal is based largely on the interest American collectors have shown in these objects, the majority of which are purchased on the art market and then acquired by museums through donations and bequests.

The positions of two museums: Case studies

Through activist associations[4], Nepal has requested the return of antiquities from the Metropolitan Museum of Art (the Met) and the Art Institute of Chicago (AIC), two museums that responded differently to its requests.

A temple pillar decorated with a Shalabhanjika Yakshi sculpture dating from the 13th century was acquired by the Met in 1988 (The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2023). It is believed to have come from the Itumbaha monastery in Kathmandu, where it was stolen between 1984 and 1985 (Schick, 1998), according to local accounts and photographic archives. Despite limited evidence on the exact date it was exported, Nepal requested its return, arguing that the pillar had been looted and exported after the country ratified the UNESCO Convention in 1976. In 2023, following further research by the Met, an agreement was signed with Nepal to repatriate the pillar. Despite the lack of concrete evidence that the object had been illegally exported, the Met demonstrated a proactive policy of restitution and covered the cost of transport.

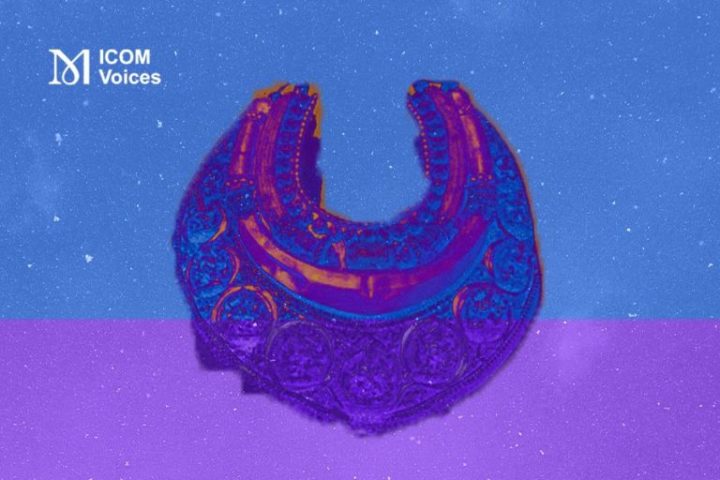

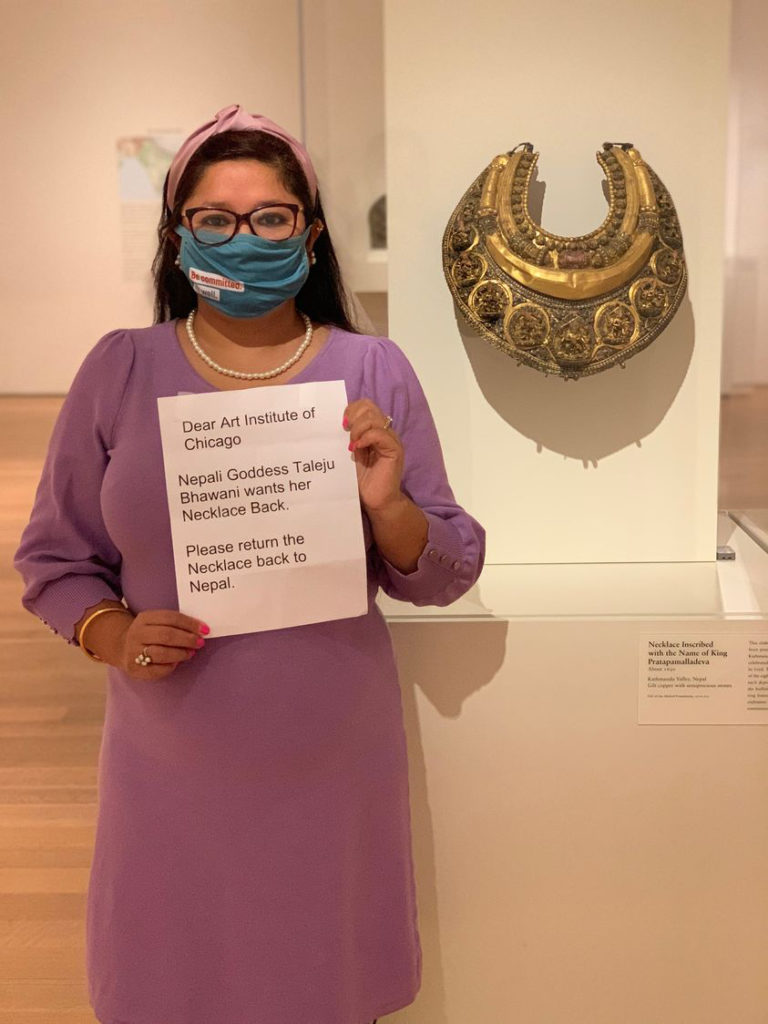

The Art Institute of Chicago has not taken the same approach. The necklace of the goddess Taleju Bhawani, dating from the 17th century, has been on loan from the Alsdorf Foundation since 1976 (Art Institute of Chicago, 2024). On display in the museum’s collections since 2010, its return was requested in 2021.[5] Manuscripts have confirmed its origin, proving that it went missing after an inventory reconciliation[6] conducted in 1970 (Nayyar, 2023).

Nepal used this evidence to request the necklace’s return. In response, the AIC demanded proof of its illicit export. Under a 1976 Nepalese law, based on UNESCO’s 1970 guidelines, mere proof of provenance is not sufficient to establish the illegality of an item’s export and acquisition. As a result, in 2024, the restitution process is still ongoing.

Unfortunately, the Nepalese government provides little funding for restitution initiatives, forcing activists to seek external funding. Lack of government support is a major obstacle, as state assistance is essential in building cases and conducting relations with embassies. The absence of a dedicated government unit makes it harder to inventory stolen objects, with bureaucratic red tape and a lack of legal resources further hampering requests for restitution. As a result, citizen initiatives are of vital importance in initiating a dialogue with foreign institutions and engaging with them on their ethical responsibility (Agrawal, 2024). Using social media and the press remains the most effective way of raising public awareness.

In the absence of legal obligations, museums may adopt positions influenced by ethical and diplomatic concerns. Although questions remain about the ethical responsibility of museums, particularly with regard to their technical and financial involvement in the process of repatriating goods, this has not prevented a large number of restitutions carried out in recent decades.

However, requests for restitution can sometimes come up against a strict application of the law, creating an imbalance between the parties. In addition, the nationalist approach of activists may not convince all museum professionals and may influence their willingness to engage.

Conclusion

Museum ethics have evolved in recent decades, largely under pressure from public opinion and from countries reclaiming their cultural treasures.

The traffic of Nepalese antiquities, and of cultural goods in general, highlights the importance and influence of museums. Through their restitution practices and changes in their acquisition and provenance research policies, museums can have a major influence on the ethical conduct of actors in the art market and this contributes to the fight against illicit traffic of cultural goods.

Museums are increasingly turning to alternative methods of resolving disputes. Among these approaches, mediation and long-term loans offer ways of fostering intercultural dialogue and finding common ground without resorting to long and costly legal proceedings.

Transparency and international cooperation, as well as the adoption of rigorous ethical policies, will be essential to ensuring that museums remain respected and credible institutions working to preserve our collective history.

Notes

[1] UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property, Paris, 14 November 1970 (entry into force 24 April 1972).

[2] UNIDROIT Convention on Stolen or Illegally Exported Cultural Objects, Rome, 1995 (entry into force 1 July 1998).

[3] In the United States, the American Alliance of Museums (AAM) and the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD) are also very influential. The AAMD updated its guidelines in 2008 to align its acquisition practices with the 1970 UNESCO Convention (The Association of Art Museum Directors, 2013).

[4] Two associations are very active in Nepal: the Nepal Heritage Recovery Campaign (NHRC) and Lost Arts of Nepal.

[5] In 2021, Sweta Gyanu Baniya, a professor at Virginia Tech, spotted the artefact while visiting the AIC. Explaining how moved she was upon seeing it, she said, ‘Traces of vermilion pigment used in Hindu worship rituals are still visible on its surface’ (Al Jazeera, 2021). She immediately informed Lost Arts of Nepal and NHRC, who relayed the information to the Nepalese authorities.

[6] Verification of a collection inventory.

References

Agrawal, S. (2024) ‘Online Activists Are Driving the Fight to Get Stolen Artifacts Repatriated to Nepal’, ARTnews.com, 20 February. Available at: https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/nepal-stolen-artifacts (Accessed: 30 March 2024).

AlJazeera (2021) ‘How did it come here?’: Nepal seeks to bring home lost treasures, Al Jazeera. Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021//nepal-lost-treasures-artefacts-stolen-gods (Accessed: 11 February 2024).

Art Institute Chicago (2024) Necklace Inscribed with the Name of King Pratapamalladeva, Art Institute of Chicago. Available at: https://www.artic.edu/necklace-inscribed-with-the-name-of-king-pratapamalladeva (Accessed: 2 March 2024).

Frigo, M. (2016) Circulation des biens culturels, détermination de la loi applicable et méthodes de règlement des litiges. La Haye: Academie de Droit International de La Haye.

Nayyar, R. (2023) Art Institute of Chicago Under Scrutiny Over Sacred Nepali Necklace, Hyperallergic. Available at: http://hyperallergic.com/art-institute-of-chicago-under-scrutiny (Accessed: 11 February 2024).

Nepalese Culture and Religion (2017) Cultural Atlas. Available at: https://culturalatlas.sbs.com.au/nepalese-culture (Accessed: 16 March 2024).

Potard, M. (2016) La difficile évaluation du trafic d’œuvres d’art, Le Journal Des Arts. Available at: https://www.lejournaldesarts.fr/la-difficile-evaluation-du-trafic (Accessed: 31 March 2024).

Schick, J. (1998) The gods are leaving the country: art theft from Nepal. 1. Engl. ed., rev. Bangkok: Orchid Press.

The Association of Art Museum Directors (2013) Introduction to the Revisions to the 2008 Guidelines on the Acquisition of Archaeological Material and Ancient Art.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art (2023) The Metropolitan Museum of Art Returns Sculptures to Nepal, The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Available at: https://www.metmuseum.org//2023/nepal-return (Accessed: 11 February 2024).