Arbresha Ibrahimi

Ph.D. Architect, teaching assistant at the Department of Architecture, Faculty of Engineering at International Balkan University in Skopje, and collaborator at Young Design Circle at WDO

Museums have no borders,

they have a network

June 5, 2024

Keywords: Museums, Skopje, Urban Renewal, Positive Change, North Macedonia

The government’s involvement in the development of Skopje’s museums is an obstacle to the authentic representation of the city’s rich multicultural and multi-ethnic tapestry – the very essence of its most valuable asset. The origins of Skopje’s fragmentation can be traced back to its inception, with the historical and archaeological sites Skopje Fortress and Scupi locality serving as primary catalysts for the city’s complex identity. The intricate historical narrative of Skopje unfolds across numerous epochs, from the ancient Dardanian Kingdom to its current iteration as North Macedonia. Influences from Roman, Byzantine, Bulgarian and Ottoman governances have contributed to the construction of Skopje’s diverse identity. These shifts in rulers have not only shaped Skopje’s architectural and urban panorama but have also left an indelible imprint on its cultural and social fabric. Skopje has gone through periods of affluence and adversity, navigating through the rise and fall of various powers. Its current identity within North Macedonia is a testament to its quest for independence and self-determination, particularly following Yugoslavia’s dissolution. Contributing factors to the city’s fragmentation include natural disasters like fires, floods, and earthquakes, along with conflicts such as the Balkan wars, inter-ethnic and inter-religious strife, political discord with neighboring countries, and mismanagement of capital investments. Each event in Skopje’s history has played a pivotal role in shaping the city’s identity. In the pursuit of establishing a national state in a multi-ethnic territory, the state’s political ideology strategically establishes institutions, particularly museums, to propagate its agenda. Nevertheless, government control over museums poses the danger of turning them into entities entirely at the service of a political agenda. Several museums have been created in the last decade, but this does not necessarily indicate an opening up of possibilities in the field if these museums cannot be independent in terms of content.

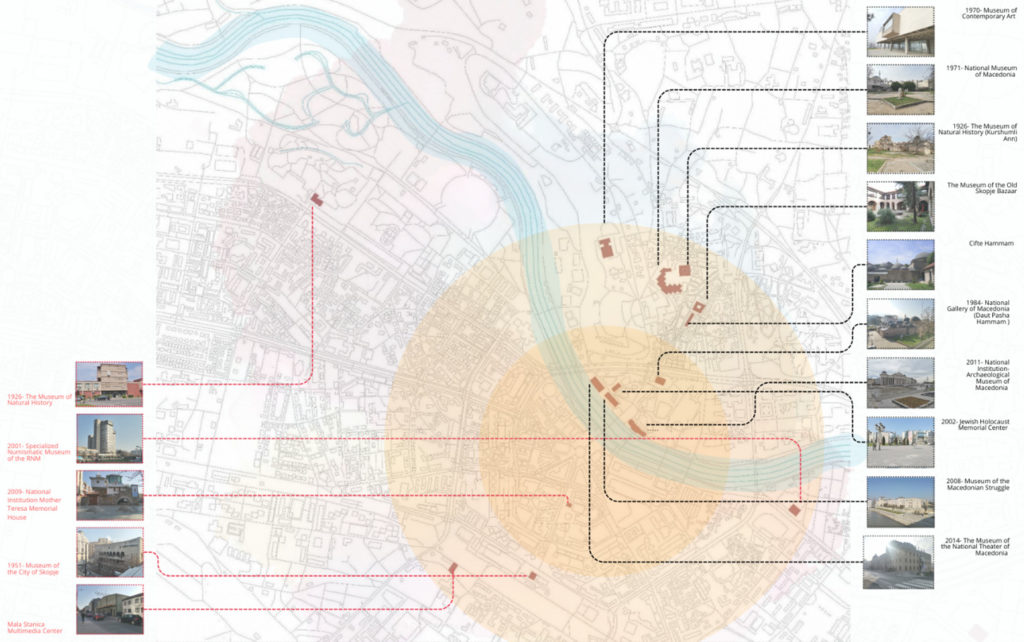

The influence of museums extends beyond exhibition spaces, often serving as focal points for urban revitalisation. Skopje’s museums are primarily concentrated in and around the city center, with their importance based on their proximity to the Vardar River – specifically, the upper and lower segments. Along the upper Vardar River, museums have distinctive Ottoman and modern architectural styles, a continuation of the North Macedonian architectural style showcased in the ‘Skopje 2014’ project. The ambitious ‘Skopje 2014’ urban planning and architecture initiative has its roots in politics, as it was proposed under the leadership of the conservative right-wing, which began implementing it before a change of government led to the halting of the project. This extensive program encompasses architecture, urban planning, and art, all with the overarching goal of rejuvenating the core of Macedonia’s capital. Conversely, museums downstream of the Vardar River predominantly showcase modern architectural designs, blending elements of socialist and brutalist architecture. Overall, each museum provides a unique perspective on the city’s architectural evolution (Fig. 1).

This blend of architectural styles and buildings not only enhances the cultural landscape of Skopje but also serves as a tangible reflection of its complex history and identity. Each museum stands as a testament to the diverse narratives that have shaped the city over centuries, making Skopje’s museum district a stimulating destination. A museum district possesses the potential to act as a hub for tourism, cultural enrichment, and economic development within a city. This potential extends to fostering collaboration and communication among different departments within museum staff, between the museum-serving community, and inter-institutional cooperation at local, regional, or global levels. Unfortunately, such collaboration has historically been limited, primarily due to the control exerted by the dominant government party over museums and their engagements or alliances with the community and other institutes in Skopje.

When strategically planned and effectively managed, a museum district has the ability to draw visitors, stimulate the local economy, and enhance the overall vibrancy of the community. Moreover, it can directly contribute to urban revitalization by prompting investments in infrastructure, public spaces, and transportation. This development not only elevates the aesthetic appeal of the area but also makes it more enticing for both residents and visitors. The synergy created through such strategic planning can lead to a positive transformation, transcending the challenges posed by historical governance influences. Despite government control, Skopje has fortunately been able to benefit from these changes. However, I would argue that without the limits imposed by such control, the city would have been transformed even more and the interactions between departments and institutions previously mentioned would have been facilitated.

The current state of museums in Skopje remains highly precarious, primarily due to significant control exerted by dominant political parties in the government. The frequent government turnover in the country further compounds the situation, leading to staff changes depending on the political party in power. This dynamic results in a lack of continuity in museum projects. Consequently, aside from occasional visits organised by primary or secondary schools and sporadic workshops for children or events such as March 8 (International Women’s Day), other activities are exceedingly scarce.

Recognising the urgent need for revitalisation and sustainability, I propose incorporating activities aligned with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). By integrating these activities, I believe museums can actively connect with their chosen SDGs and contribute to fostering a sustainable environment.

This strategic approach seeks to break the cycle of infrequent and disjointed initiatives by providing museums with a framework that aligns with broader global sustainability objectives. Through the adoption of activities suggested by the SDGs, museums in Skopje can transcend the challenges posed by political dynamics and government control, contributing to a more stable and impactful cultural landscape.

Looking towards the future, the prospects for museums in Skopje open up a critical opportunity for transformative growth and cultural enrichment. However, the existing challenges in communication and collaboration, deeply entwined with political dynamics and historical complexities, need to be seen as a call to action rather than insurmountable barriers. By embracing strategic approaches and aligning with global sustainability goals, these institutions can transcend historical barriers and become key players in shaping a more inclusive, resilient, and dynamic community for generations to come.