Courtney Traub

Senior Editor at Museum International, journalist and travel writer

Museums have no borders,

they have a network

December 2, 2025

As it has in the past, the Norwich-based Centre has planned multiple exhibitions as part of the thematic season, exploring its key themes from several cultural, ideological and curatorial angles. A major highlight of the current programme is a solo exhibition from Ethiopian artist Tesfaye Urgessa, entitled Roots of Resilience and showing through 15 February, which I was invited to visit during a press preview. Curated by John Kenneth Paranada[1], Curator of Art and Climate Change at the Sainsbury Centre, the show was staged with the support of the Cheng-Lan Foundation in Hong Kong and the Saatchi Yates gallery in London.

Urgessa, who completed an artist’s residency at the Sainsbury Centre earlier this year, produced a series of new paintings and sculptures specifically for the Centre that were intended to be in dialogue with works in the museum’s permanent collection, including paintings from Pablo Picasso and Francis Bacon. The newly commissioned series reflects on the global refugee crisis and experiences of migration, underlining the violence and trauma of geographical displacement – but also the resilience and dignity of those who experience it.

Urgessa drew on traditional Ethiopian aesthetic codes and cultural tropes in imagining the dramatic human figures that occupy the centre of his works. Cubist elements are also evident in the paintings and sculptures, placing them in dialogue with Pablo Picasso – a predecessor that Urgessa directly acknowledges. Picasso’s Woman Combing Her Hair (1906), featured in the Sainsbury Centre’s permanent collection, is placed side by side with Urgessa’s own interpretation of the work, while Francis Bacon and German Neo-expressionism are also key influences.

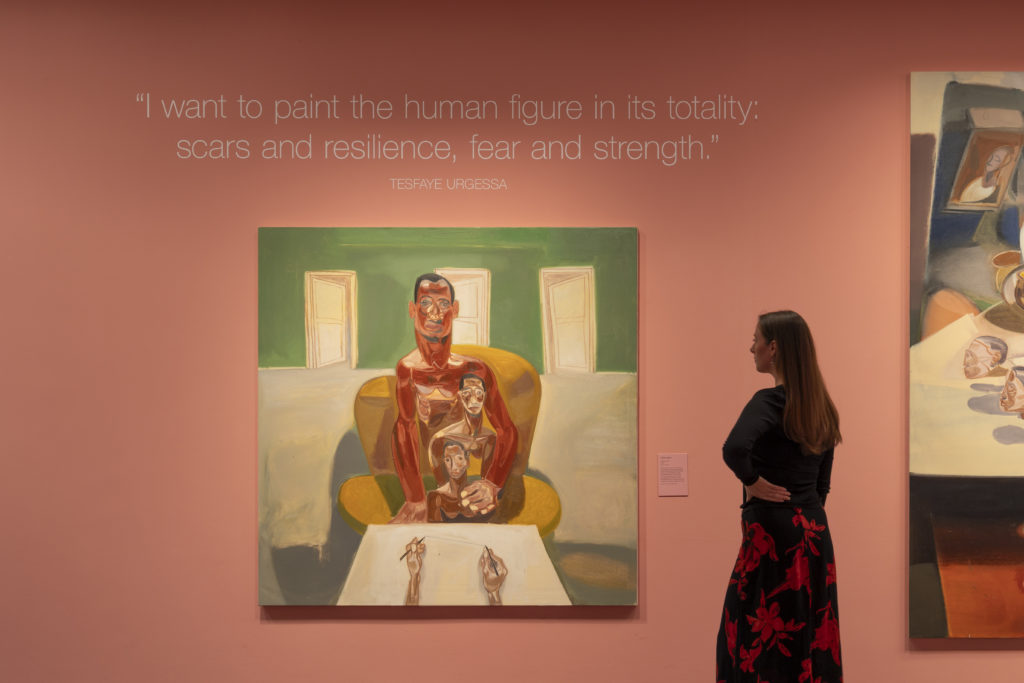

Yet rather than contorting his human subjects to abstraction (as Picasso so often had) Urgessa infuses his own subjects with a deep sense of emotion, vulnerability, strength and quiet defiance. For Curator Ken Paranada, ‘Tesfaye’s paintings are fearless. They hold us in that raw place between horror and tenderness. His fleshy, contorted figures seem almost under the skin, carrying the shock of Francis Bacon and the anti-war cry of Guernica, yet speaking in a language entirely his own’.

Several of the paintings speak directly to the alienating and potentially traumatic experiences of migration, racism, and ‘processing’ procedures that often tend to treat refugees as numbers and statistics rather than individuals. Urgessa’s work centres the individuality of such experiences, pushing back against the dehumanisation and abstraction that often dominates in political rhetoric about asylum seekers.

In Luminous Life, a father figure stands with his two children – all nude, suggesting their vulnerability – in front of a bureaucrat’s desk. The bureaucrat is represented by two bony hands, recalling those of Egon Schiele’s work, clutching writing implements in each and drawing a line across the table.

‘That line is both an act of power and an act of exclusion’, Urgessa said in an artist’s statement. ‘It is about the way history, especially in the Western world, has drawn lines through slavery, colonialism, segregation, through double standards that kept opportunities open for some while shutting doors for others’.

And yet, three open doors occupy the frame’s horizon, suggesting the possibility beyond the confines of the processing centre. ‘For me, this tension between being defined by history and still carrying the possibility of change is what this painting is trying to hold’, the artist remarked.

Other works in the show are more allegorical, inviting reflection not only on what people leave behind when forced to flee their homes, but also what they carry with them. First Flame features a contorted figure of a woman, bare-breasted and hunched over a series of broken objects as she stares squarely ahead. In one hand, she holds a clutch of bright green leaves. In the background, a less prominent female figure is breastfeeding her infant; the mother and child motif repeats in many of the works featured in the show.

The broken objects in the foreground, Urgessa explained, are ‘things which are identifiable and not identifiable… things that feel like remnants of an old life, yet markers for a new one’. As for the green leaves, which the woman almost seems to be listening to, they might represent ‘the first flame, the small spark that could grow into a different era, a different life’.

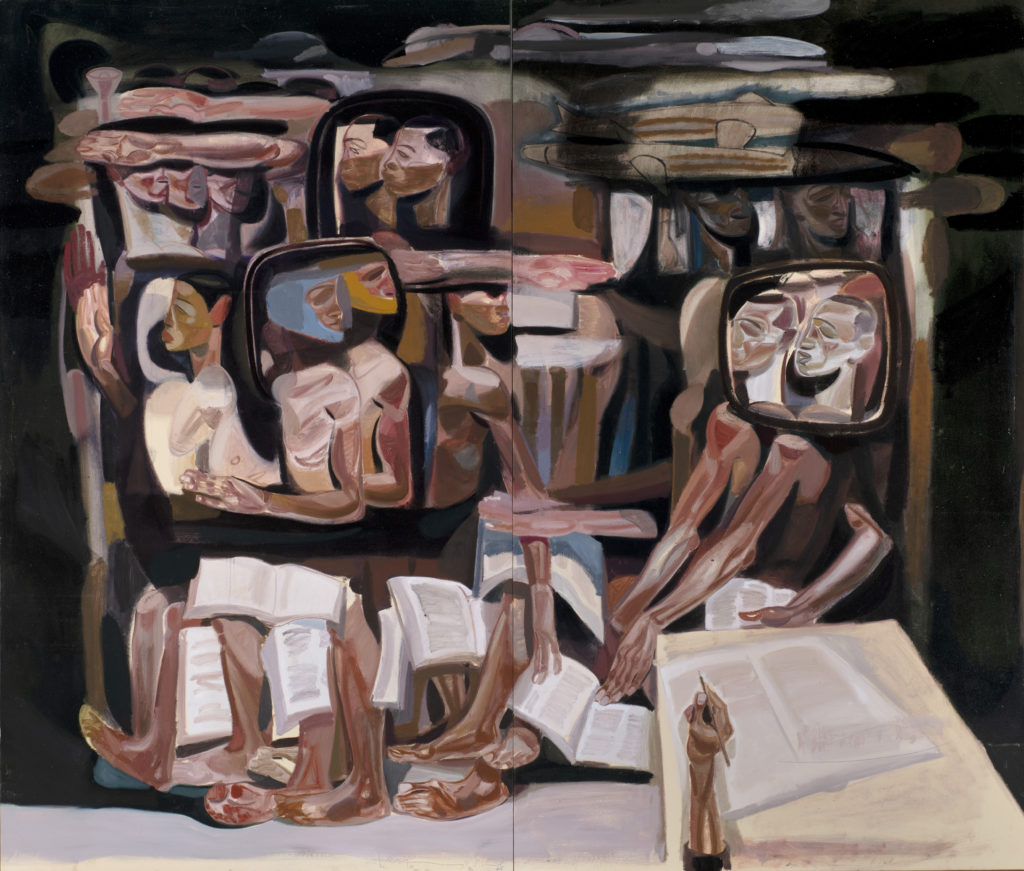

No Country for Young Men

In addition to works commissioned by the Sainsbury Centre, one large-scale painting in the solo show, entitled No Country for Young Men, 31, is especially striking – and first gained international attention when Urgessa represented Ethiopia at the 60th Venice Biennale in 2024. One in a large series of works that address the refugee crisis in an almost epic mode, #31 depicts a group of people tightly huddled together, facing a disembodied hand holding pen and paper. Open books lie at the feet of many of the figures, perhaps representing knowledge brought from home, or knowledge that must be mastered to survive in one’s new prospective home. Some of the faces in the tableau appear as reflections in mirrors; Urgessa told me at the press preview that he conceived the mirror images as a potential way for audiences to see themselves reflected in the work.

Urgessa began the series in 2016, at the height of the refugee crisis. ‘At that time, he was assisting his wife at a centre for traumatised children and families who had undergone the journey of migration’, said Ying-Hsuan Tai, Director of Asia at the Saatchi Yates Gallery, who recommended Urgessa’s work to the Sainsbury Centre and secured support for the exhibition by the Cheng-Lan Foundation.

‘He mentioned that the sound of [the refugees’] footsteps stayed with him at night before sleep during that period, and it became the catalyst for this series’, she added.

The painting was later acquired by the Cheng-Lan Foundation, a non-profit which is dedicated to working with artists whose practices engage with migration, memory and cultural continuity, Tai noted. ‘Through this collaboration, we are now finalising an acquisition for the Sainsbury Centre’, she said – marking the first time one of Urgessa’s works will find a permanent home in a public museum in the UK.

Reflecting on violence and empathy: Education initiatives

One clear ethos at the heart of Urgessa’s show, and the broader season at the Sainsbury Centre, is to get audiences to actively reflect on their potential roles in both violence and its best antidote, empathy. Paranada told me that education and outreach initiatives to encourage audiences, and especially young people, to engage and reflect on such issues are a cornerstone of the Can We Stop Killing Each Other? programme. ‘Together with the Learning Team at the Sainsbury Centre, we are launching a new project with artist Jack Young called Archaeology of the Future’, he said. ‘This one-day workshop will invite parents and their teenage children (aged 14-18) to work with Jack through sculpture, storytelling, and philosophical discussion to imagine a world beyond conflict’, he added, noting that participants will be recruited through local school networks, the museum website and social media channels. ‘What excites me most is the way this project can open new channels of communication between young people and their parents, outside of their usual rhythms at home. It also promotes intergenerational dialogue at a moment when young people, many of whom will be voting for the first time in the next election, are finding their political voice.’

__________________________________________________

Roots of Resilience: Tesfaye Urgessa is open through 15 February 2026. A selection of Urgessa’s works will then travel to the Red Brick Art Museum in Beijing from March 2026. Can We Finally Stop Killing Each Other? runs through 17 May.

[1] John Kenneth Paranada published an article entitled ‘A Path Forward: Curating Art & Climate Change at the Sainsbury Centre, University of East Anglia’ and available in Open Access on Taylor and Francis website in the ‘Museum Sustainabilities’ double issue of Museum International (Vol. 75).