This is an extract of the article ‘The future of research’ by Frank Howarth, originally published in The Future of Natural History Museums, edited by Eric Dorfman.

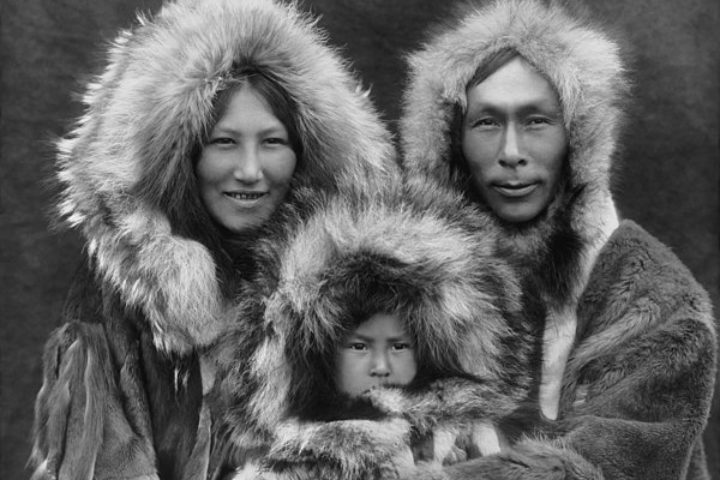

Many of the world’s longstanding natural history museums have extensive collections of materials created by indigenous peoples, and, in many cases, collections of whole bodies and body parts of such peoples.

In Australia, New Zealand, the United States, and Canada, active and extensive programs of repatriating human remains have been undertaken. Progress on this has been much slower or in many cases non-existent in Eastern and Western Europe.

The origins of these collections are as complex as the origins of anthropology itself, and reflect many factors at work amid the building of empires. Objects were added to anthropological or ethnographic collections for a wide range of reasons. Some were aesthetically appealing to a Western colonial eye; others were more prosaic and practical, including objects of daily life. Still others were weapons or fetish and ritual objects. These factors are summarized well in the introduction to Objects and Others (Stocking, 1988).

In the second half of the twentieth century, several developments began to challenge anthropological orthodoxy. Much of this was associated with the increasing demands from indigenous peoples for a greater say in what happened to material created by them and their ancestors. In parallel with this were challenges from within anthropology itself. In Australasian Science, anthropologist Kirrilly Thompson writes of early twentieth-century Polish anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski:

Malinowski’s personal diaries… show a man struggling between “us and them,” between the old regime of a racism legitimating colonialism and asserting difference, and a new regime emphasizing sameness and questioning the superiority that any one culture has over another. (Thompson, 2016)

Both challenges had a significant impact on anthropological research and activities in natural history museums, most notably, the growing role of indigenous peoples in determining how they were studied and how their cultural heritage was treated and communicated with the wider world.

One factor more than any other seems to shape future collection-based museum research in anthropology. This is the shift in mindset on the part of some museums whereby they no longer consider the museum as “owning” the collections of the material culture of indigenous peoples, but, rather, as serving as custodians of the material, primarily for the creator communities and their descendants. Custodians have different and greater obligations than owners. Foremost is the obligation to involve those creator communities in key decisions pertaining to the use of collections, and the research conducted on them.

In this way, creator communities are seen as equals in the research, as collaborators, rather than merely the subjects of study. Given this, communities might be asked which elements of their cultural heritage they would like a museum to collect and hold. Major institutions in Australia and New Zealand, as well as the British Museum, work with Pacific communities to create objects that tell stories and preserve culture. A prime example of this is the Australian Museum’s effort to commission works from the people of Erub (Darnley Island) in Torres Strait. Blog posts demonstrate the process by which the Erub people decided what stories to tell through the objects commissioned by the museum and made by them (Australian Museum, 2012).

A key question in anthropology is how modern humans migrated from Africa to the rest of the world. New and earlier dates for humans in various parts of the world, alongside better understanding of human genetics, suggest that the move out of Africa occurred in waves and was much more rapid than had previously been the case. By way of example is the ongoing uncertainty over how the first humans arrived in North, Central, and South America. Curry (2012) writes, “For decades, scientists thought that the Clovis hunters were the first to cross the Arctic to America. They were wrong—and now they need a better theory.” In www.Smithsonian.com, on 21 July 2015, Helen Thompson writes of more recent genetic research:

The prevailing theory is that the first Americans arrived in a single wave, and all Native American populations today descend from this one group of adventurous founders. But now there’s a kink in that theory. The latest genetic analyses back up skeletal studies suggesting that some groups in the Amazon share a common ancestor with indigenous Australians and New Guineans. The find hints at the possibility that not one but two groups migrated across these continents to give rise to the first Americans. (Thompson, 2015)

The combination of ongoing specimen discovery and subsequent genetic work means that collections of early humans held in natural history museums have ongoing significance for such research, and museums have an obligation to keep pace with this rapidly changing field, and accurately represent levels of scientific uncertainty to their visitors.

One of the largest and most enduring museum anthropology programs is that at the American Museum of Natural History, whose research program manifests engagement not only with contemporary culture, but also with complex interdisciplinary issues. This is exemplified in a statement regarding a 2016 conference at the museum on the emergence of HIV:

The conference presents international research on the biological, epidemiological, and social contexts of the emergence of HIV/AIDS. Bringing together specialists from the fields of virology and molecular biology, epidemiology and public health, and history and anthropology, this conference provides the context for cutting-edge, multidisciplinary insights into one of the most devastating global infectious disease pandemics of the twentieth century. (American Museum of Natural History, 2016a)

Anthropology and climate change are referenced in a description of a workshop held at the museum in 2013 and organized in conjunction with the National Museum of Australia. The workshop was charged with “exploring how museums can engage communities in ways that foster understanding and help with adapting to processes of climate change” (American Museum of Natural History, 2013).

A logical extension of indigenous communities’ greater influence in museums is those communities’ creation of their own museums in Western countries. Such museums speak about indigenous cultures in the cultures’ own words, rather than from the detached, usually non-indigenous voice of the science-based natural history museum. A ground-breaking example of this is the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian. The existence of two major museums under the Smithsonian umbrella holding major collections of American Indian cultural heritage and associated research programs, the other being the National Museum of Natural History, has led to tensions based on their different research approaches. This is well summarized by Duarte (2012) in Repatriation and the Smithsonian. She writes:

The Smithsonian Institution’s involvement in the fight for control of indigenous history can be traced to many cases of disagreement between researchers and indigenous people throughout history, yet no other instance of its involvement has been more indicative of this larger debate than the Smithsonian’s internal debate currently being enacted through the repatriation philosophies and practices of the National Museum of Natural History and the National Museum of the American Indian. While each museum has vastly different histories that have influenced their relationships with indigenous people, both choose to advance contrasting conceptions of property that purport either the political stance of science or that of indigenous peoplehood.

In the case of these two Smithsonian museums, the approach each has taken is consistent with their mission, goals and core values. The National Museum of Natural History is a fundamentally research based institution with a deeply seeded [sic] mission of providing access to knowledge to all mankind. The National Museum of the American Indian is the self-proclaimed, “Museum Different,” and as such has intentionally deviated away from the traditional role of the museum seeking to serve indigenous communities and the greater public as an honest and thoughtful conduit to indigenous culture, present and past.

Perhaps the single most important aspect of the National Museum of the American Indian’s philosophies and practices regarding the disposition of indigenous remains and cultural property is its focus on collaboration between indigenous people and researchers at every step of the process. This valuable aspect should be applied to the greater political debate over the control of indigenous history. (Duarte, 2012, p. 41)

Pulling it all together: the future of anthropology in natural history museums

Of all the research areas in natural history museums, anthropology is in the process of the most profound change. While the subjects of biological and geological research do not have a voice (although in the case of animals, they certainly have human advocates), the subjects of anthropological research do have a voice and they are using it. Collaborative studies, such as using indigenous people’s DNA to trace human migration, and collaborative addressing of problems, like the impact on indigenous peoples of global warming, are the way of the future.

Overall conclusions about the future of research in natural history museums

The successful natural history museum in the twenty-first century is revealed in up-to-date displays and a web presence that deals in a balanced but fearless way with contemporary issues. All staff, but most particularly research staff, are engaged with their work, their colleagues, and their institutions.

Those natural history museum researchers who embrace change, welcome collaboration, and work in partnership with their communities and stakeholders will thrive. They will be using new analytical techniques, harnessing the power of the digital realm, and collaborating with universities and citizen scientists. They will be focused on the problems of today and tomorrow. They will have engaged new funding partners who share their values, and distanced themselves from those who don’t.

Research cultures will continue to evolve rapidly. Researchers who once saw themselves working for a discipline, or only with their peers in that same discipline, now see themselves as working for a museum and a community. A lifetime studying one animal group will be a thing of the past. Links between research, collections, and public engagement will be much stronger, but also innovative and adept. New ways of using collections will be found by researchers inside and outside museums. Communities will have a greater say in how those collections continue to grow. Digital access to and use of collections will grow exponentially.

Natural history museum research can and does have a bright future, one that is all about relevance, engagement, and collaboration.

–

Frank Howarth trained as a geologist, completing a BSc in Geology at Macquarie University, followed by a Master of Science and Society from the University of New South Wales, focusing on Science and Biotechnology Policy. Frank joined the NSW government in 1981, holdings positions with the Department of Industrial Development and Decentralisation, NSW Science and Technology Council, the Public Service Board, and the Roads and Traffic Authority. In 1996, he became Director and Chief Executive of the Royal Botanic Gardens and Domain Trust. In September 2003, he spent six months as Executive Director, Policy and Science, at the NSW Department of Environment and Conservation, before taking up the role of Director of the Australian Museum from February 2004 to 2014. He is currently President of Museums Australia.

The Future of Natural History Museums, edited by Eric Dorfman and published by Routledge, is part of ICOM Advances in Museum Research, a new monograph series edited by ICOM. Natural history museums are changing, both because of their own internal development and in response to changes in context. The Future of Natural History Museums considers these changes and the reasons behind them and begins to develop a cohesive discourse that balances the disparate issues that our institutions will face over the next decades.