Alejandra Linares-Figueruelo

PhD candidate at the University of Barcelona

Museums have no borders,

they have a network

December 18, 2023

Keywords: Satellite Museums, Cultural Regeneration, Community Engagement, Urban Transformation, Global-Local Dynamics

Global Echoes in Local Spaces: The Satellite Museum Phenomenon

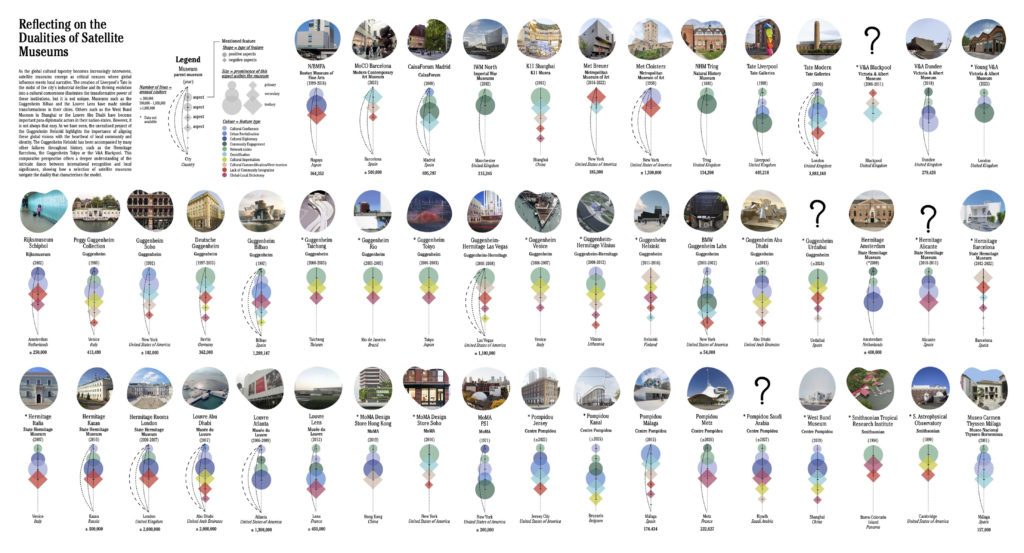

In today’s interconnected world, satellite museums stand as centres of cultural confluence, transcending geographical and cultural boundaries. These offshoots, ranging from monumental institutions such as the Louvre Abu Dhabi to more local initiatives such as the Louvre Lens, are not mere extensions, but unique entities reflecting their host communities.

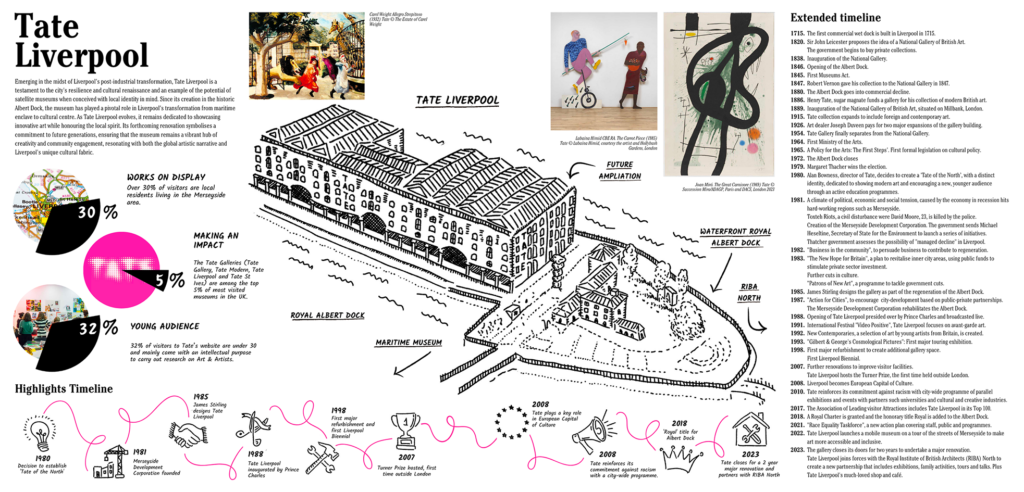

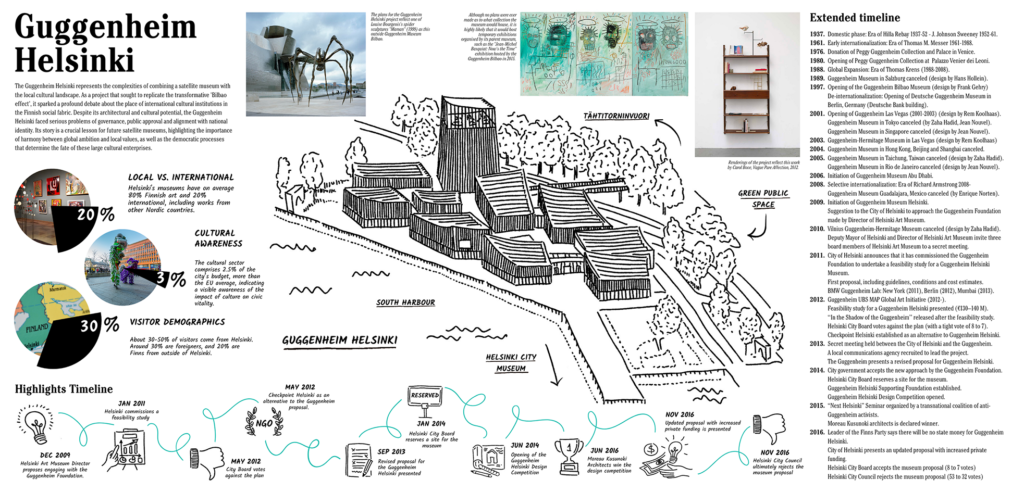

Established in 1988, the Tate Liverpool emerged during Liverpool’s period of economic and social challenges since the 1970s. Set against the backdrop of political strife during the Thatcher era, the museum became a symbol of urban regeneration, playing a key role in transitioning Liverpool from an industrial hub to a cultural center, contributing to the city’s cultural democratisation and diversifying its art scene. Over twenty years on, the Guggenheim Helsinki project (2011-2016) would spark intense debates on cultural globalisation versus local identity, focused on concerns over the potential commercialisation and erosion of local cultural heritage. The project became the focus of a social debate, encapsulating the challenges of integrating a global cultural institution with local and national cultural identity.

This juxtaposition of Liverpool’s success against Helsinki’s struggles poses the question: What are the key factors that distinguish a successful satellite museum project from one that falters? In this article, we aim to examine the nuanced dynamics of satellite museums, shedding light on their unique ability to weave the global tapestry of cultural heritage into the intricate patterns of local culture.

Community Resonance and Urban Transformation

The success of a satellite museum hinges on its ability to effectively engage with its community, which extends beyond attracting visitors, it encompasses encouraging participation and the reflection of community identities. The Tate Liverpool exemplifies this approach, having transformed itself into a vibrant cultural hub that resonates with its inhabitants. It has played a pivotal role in enriching Liverpool’s cultural scene, from showcasing local artists to contributing to the first Liverpool Biennial (1998). These efforts, combined with programmess encouraging local artistic and community participation, have further strengthened its integration into Liverpool’s social and cultural fabric (Lorente 1996). In contrast, the Guggenheim struggled to connect with the community due to its lack of inclusive and participatory approaches. This led to public opposition to the construction of the museum and highlighted a misalignment with Helsinki’s cultural values and policies. The project’s failure to engage with local artists and community groups, missing opportunities for collaborative programming and dialogue, resulted in significant controversy (Ponzini 2018).

However, the transformative influence of satellite museums goes beyond community engagement, they can also have a significant impact on urban regeneration and economic vitality, always determined by their cultural policy and governance structures. The Tate’s achievements can be attributed to its governance model, closely aligned with Liverpool’s cultural and urban development goals. Its approach of collaborative governance, involving local stakeholders in decision-making, has ensured responsiveness to community needs, fostering shared ownership and identity (Lorente 2016).

Architectural Identity and the Balance of Global-Local Dynamics

The architecture of a museum is more than a physical structure; it embodies the institution’s identity and its relationship with its environment. Satellite museums exemplify the complex interplay between architectural design, global-local dynamics and sustainability, crucial factors that contribute to their success or struggles. The Tate Liverpool, housed in the historic Albert Dock, was a successful architectural adaptation and symbolises Liverpool’s transition from a historical port to a cultural hub. This architectural decision mirrors Tate’s success in balancing its global brand with local culture. Its exhibitions and programs also cater to both international and local audiences. In contrast, the Guggenheim faced significant challenges in aligning its global appeal with Helsinki’s unique architectural character and cultural context. Attempting to replicate the success of the Guggenheim Bilbao, the project struggled with design resonance and establishing a sustainable financial model appropriate for Helsinki’s cultural and economic environment. This led to financial sustainability challenges and the project’s eventual cancellation, highlighting the complex tensions in satellite museum projects between global identity and local responsibilities.

This comparison evidences the need for satellite museums to be not just economically viable but also culturally resonant and socially responsible, ensuring their long-term sustainability and positive impact on the community. This dynamic is crucial in understanding how these museums navigate their roles within the global network of cultural institutions while remaining rooted in their local environments.

Navigating Future Pathways for Satellite Museums

This comparative analysis aims to highlight some of the factors that contribute to the success or failure of satellite museums. The Tate Liverpool managed to become a sustainable cultural institution that resonates with both global and local audiences. Conversely, the Guggenheim Helsinki project serves as a cautionary tale, underscoring the complexities and challenges inherent in establishing a satellite museum. Its struggle emphasises the critical importance of a nuanced approach that prioritises an understanding of the socio-political context and architectural and operational sustainability in order to integrate the needs and values of the local community into the project.

Looking forward, satellite museums stand at a pivotal juncture in the evolving cultural landscape. They possess the unique potential to redefine cultural experiences and community interactions, transcending traditional boundaries and expectations. As the cultural sector continues to evolve, the lessons learned from the Tate Liverpool and the Guggenheim Helsinki will be invaluable in guiding the development of satellite museums, ensuring they remain vibrant, relevant, and integral components of both the global art community and their local environments.

Alejandra Linares-Figueruelo has published an article on satellite museums entitled “Cultural Franchises or Franchising Cultures? The Case of the Hermitage Barcelona” in Museum International: Open Edition published in December 2022 (Vol. 74. No. 293-294, 2022).

If you are an ICOM member, you can access all issues of Museum International free of charge through your ICOM member space. If you are unable to access them, please do not hesitate to contact us at publications@icom.museum

References:

Alshawaaf, F. and Ponzini, D. (2020). ‘Cultural policies in the era of digital communication: The case of the Guggenheim Helsinki’, Museum International, 71(1-2), pp. 44-59. DOI: 10.1111/muse.12210.

Appadurai, A. (1996). Modernity at Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Bennett, T. (1995). The Birth of the Museum: History, Theory, Politics. London: Routledge.

Castells, M. (1996). The Rise of the Network Society. Oxford: Blackwell.

Evans, G. and Shaw, P. (2004). ‘The Contribution of Culture to Regeneration in the UK: A Review of Evidence’, Report to the Department for Culture Media and Sport, London: DCMS.

Lorente, J. P. (ed.) (1996). The Role of Museums and the Arts in the Urban Regeneration of Liverpool. Leicester: Centre for Urban History, University of Leicester (Working Paper / Centre for Urban History; 9).

Ponzini, D. (2018). ‘Urban implications of cultural policy networks: The case of the Guggenheim Helsinki’, Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 36(2), pp. 199-217. DOI: 10.1177/2399654417725074.

Ponzini, D. and Ruoppila, S. (2019). ‘Two attempts to develop Guggenheim museum in democratic Helsinki’, Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 37(1), pp. 8-27. DOI: 10.1177/2399654418789943.

Ritvala, T., Granqvist, N., and Piekkari, R. (2021). ‘A processual view of organizational stigmatization in foreign market entry: The failure of Guggenheim Helsinki’, Journal of International Business Studies, 52, pp. 282-305. DOI: 10.1057/s41267-020-00329-7.

Simon, N. (2010). The Participatory Museum. Santa Cruz: Museum 2.0.