Liu Gaoli

Research and Curatorial Fellow, National Ainu Museum; member of AVICOM

Museums have no borders,

they have a network

October 31, 2023

Keywords: immersive experience, Indigenous, biodiversity, open museum, COP15

Chaired by China and hosted by Canada, the 15th Conference of the Parties (COP15) to the United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity took place in Montréal, Quebec from December 7 to 19, 2022, with representatives from 188 governments in attendance. Beyond the confines of the Blue Zone designated for registered delegates, a variety of activities in the Green Zone and throughout the city offered open-access opportunities for a multisensory experience.

In this article, I would like to take a look back at this experience, which was immersive thanks to the physical and virtual events that were organised in spaces dedicated to exhibitions but also in the streets of the Montréal, as walking around the city was also a way of experiencing the themes of this COP15.

Experiencing Living Indigenous Rituals

The Indigenous Leadership Initiative established an Indigenous village in the Green Zone that provided a space for Indigenous peoples from the region and around the world to showcase their cultures and concerns for the lands and resources. The main stage and podium were traditional Innu Shaputuan (a big gathering tent), adjusted to accommodate more than a hundred people. In addition, there was a longhouse and a tepee modelled after housing in other Indigenous communities.

The three-day program focused on Indigenous leadership and Indigenous efforts to conserve biodiversity and was fully open to the public. It included panel discussions, art displays and traditional food stalls. Onsite vendors sold Indigenous-made and traditional art and other products.

On the opening day, an Indigenous knowledge keeper performed the Lighting of the Sacred Fire ceremony and distributed dried tobacco to the attendees. This ceremony offered a chance for the collective to present fire offerings for blessings and prayers, fostering a connection between humans and the Natural Spirit. By casting the tobacco into the fire, the message of the ceremony was relayed to the Spirit World. The sacred fire dispelled the early morning chill and bonded those present for the ceremony, even if they were previously strangers to each other. The elders told stories about their connection to their ancestry and heritage, followed by a smoke ceremony inside the Shaputuan. The touch of the plant, the smell of the smoke, and the warmth of the fire allowed us to experience a part of an Indigenous culture and helped us to feel a deep connection with nature and with each other.

Fig. 1. The Indigenous village inside the Green Zone. © Gaoli Liu

The Use of Virtual Reality

Another experience worth highlighting was the use of virtual reality (VR) technology. VR has emerged as a powerful tool to engage users and enhance learning outcomes across various industries. Its versatility and effectiveness were on full display at the COP15 where it was used to showcase sustainable initiatives and examples of Indigenous cultures.

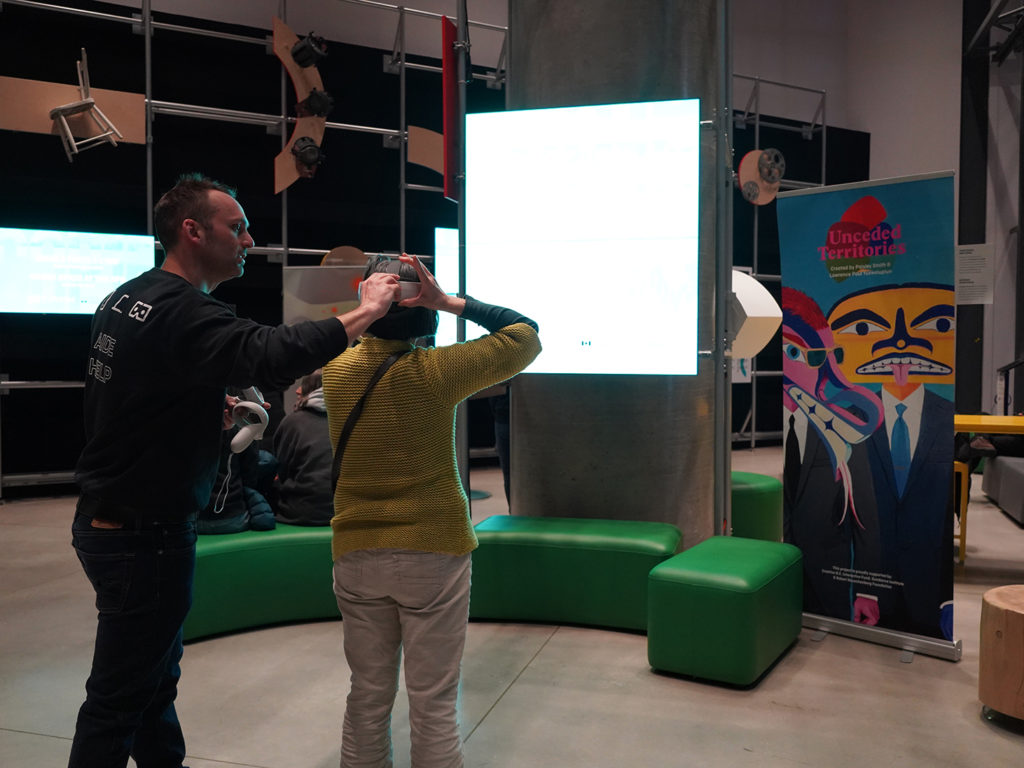

The conference featured at least two separate VR events, including a captivating display hosted by the European Union in the Green Zone, and another event took place at the National Film Board of Canada (NFB) located in the vibrant cultural and economic centre of the city. In total, visitors were treated to five or six VR programs that allowed them to connect with Indigenous cultures, reflect on the environment, and engage with the conference’s sustainability message.

Fig. 2. The VR headsets and handsets, inside the National Film Board of Canada (NFB). © Gaoli Liu

Through VR headsets and handsets, attendees were transported into a virtual world that closely resembled reality. The immersive experience provided a new level of interactivity, enabling users to explore virtual worlds and interact with digital objects and characters in ways that were not previously possible.

One of the standout VR experiences was Biidaaban, which transported users to a futuristic Toronto where nature has reclaimed the city. Through virtual reality, I found myself standing on the precipice of a building, surrounded by a wild and untamed environment. With the immersive experience, I interacted with diverse languages of the region once known as Tkaronto and engaged with written text from the First Peoples, such as Wendat, Mohawk, and Ojibway.

Plastisapiens, another VR program, allowed participants to experience empathy with plastic, the ubiquitous material that we all use. By engaging with various virtual organisms, I witnessed my (virtual) self merge with plastic, symbolizing a possible future where synthetic materials and human biology coexist. This immersive experience prompts us to reflect on our relationship with the natural world and how our environment shapes our identity, even at the genetic level.

Fig. 3. VR experience staff and participant, inside the NFB. © Gaoli Liu

In my opinion, the use of VR to promote sustainability and preserve Indigenous culture is a highly effective approach. By immersing users in a virtual environment, it allows them to focus on the content without any external distractions. This innovative technology enables users to gain unique insights and perspectives that may not be available in the real world. Additionally, VR provides a safer platform for exploring dangerous or sensitive topics. This immersive experience can raise awareness about the environmental impact of our actions and motivate people to take action.

City-wide Immersive Experiences

In contrast to the previously mentioned experiences, which were bound by time and location, visitors to the city’s primary cultural district could freely interact with street sculptures. Crafted by artists and centered on the theme of climate change, these artworks captivated people. Their imaginative designs not only drew attention but also encouraged many to touch them and take photos, fostering active participation. The area is also home to art galleries and museums that hosted exhibitions related to the same theme. Due to the timing of the conference coinciding with other artistic events, such as the Cité Mémoire and the AURA experience, people also witnessed a large public projection circuit and light show that highlighted related themes and the city’s history, providing an immersive experience and allowing visitors to explore the city in a more engaging way.

Fig. 4. A life-sized ice sculpture of a polar bear. As the ice gradually melted, the animal’s skeleton was revealed. © Gaoli Liu

Conclusion

The COP15 Montreal public space was transformed into a hub of experimentation and innovation across a variety of fields, including technology, art, and design. This transformation turned the city into an enormous immersive exhibition that showcased the marvels of biodiversity. This model could be an excellent example for a museum exhibition that combines both physical and virtual components.

While there is often debate about the merits of physical versus virtual exhibitions, the truth is that each has its own benefits. Physical exhibitions, with their tangible experiences – smells, sounds, crowds, and talks –, enhance communication and bring people together. On the other hand, virtual experiences offer an interactive way to gain a deeper understanding of a topic, blurring the boundaries between reality and fiction and providing fun and memorable experiences that actively engage visitors.

Taken together, physical and virtual components can create an immersive and unforgettable museum exhibition. By harnessing the power of both, museums can continue to push the boundaries of what is possible and offer visitors a glimpse into the wonders of our world.

Fig. 5. A street with interactive artworks, Montréal. © Gaoli Liu

Special Thanks

Délégation générale du Québec à Tokyo

Resources

https://www.canada.ca/en/services/environment/wildlife-plants-species/biodiversity/cop15.html

https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/cop15-ends-landmark-biodiversity-agreement

October 16, 2023

September 29, 2023