Claudia Porto

Museologist at the Chamber of Deputies / Brazilian Congress, independent museums consultant focusing on communication of collections, and member of ICOM Brazil's Administrative Council.

Museums have no borders,

they have a network

October 16, 2023

Keywords: cultural heritage, collections preservation, collections management, education for democracy.

In this article, I describe the swift response of the teams managing the collections in Congress, underscoring the importance of conducting an inventory and implementing a Risk Management Plan. I also highlight the initiative of the STF to publicly display fragments of the damaged items, thus re-signifying the attack. Lastly, I emphasize the importance of the senior management of public institutions such as these in recognizing the need to invest in the preservation of their collections, which themselves serve as powerful educational tools for democracy.

Attack on palaces, attack on democracy

The images featured in the newspapers of January 8, 2023, displayed disturbing scenes: shattered windows, broken furniture and equipment, vandalised artistic and historical heritage, and flooded halls. On that Sunday, thousands of supporters of the far-right former president of Brazil invaded and vandalised the buildings of the National Congress, the Presidency, and the Federal Supreme Court. The attack inflicted severe damage upon the cultural assets of these institutions. However, more than that, it posed a threat to the very democracy of Brazil. What trigged these invasions? An outrage over the election results, which, just seven days prior, had inaugurated a leftist president. A disastrous coup attempt.

Fig. 1. Facade of the National Congress with shattered windows. © Pedro França/Agência Senado

Brasilia is inscribed on UNESCO’s World Heritage List as an example of modernist urbanism and architecture since 1990. Designed by architect Oscar Niemeyer, public buildings such as the headquarters of the three republican branches are emblematic. The National Congress, which houses the Federal Senate and the Chamber of Deputies, along with the Federal Supreme Court and the Planalto Palace, collectively embody the independence and harmony among the Executive, Legislative, and Judicial branches, serving as symbols of Brazilian democracy. The geographic proximity between them facilitated the invasions.

The collections of these three Houses represent significant primary sources about national political life. They gather documents produced since the establishment of the Brazilian Parliament in 1823, including Constitutions, manuscripts, photographs, and audio-visual materials. The palaces also safeguard works by artists such as Alfredo Ceschiatti, Victor Brecheret, Di Cavalcanti, Athos Bulcão, and Marianne Peretti, in addition to furniture designed by Niemeyer, Ségio Rodrigues, and Jorge Zalszupin. Protocol gifts, offered by heads of state and diplomatic representatives visiting the country, further enrich these collections.

Fig. 2. A restorer from the Senate Museum displays the damages inflicted upon a Burle Marx tapestry. © Pedro França/Agência Senado

Damage and contamination

Numerous objects were damaged in the attack. At the Planalto Palace, a 17th-century pendulum clock made by Balthazar Martinot, a gift from the Court of France to Portugal that was later brought to Brazil by King Dom João VI, was intentionally thrown to the ground and shattered.

Even more significant were the damages inflicted upon the national heritage. A painting by Di Cavalcanti endured seven knife strikes, and a Burle Marx tapestry was torn and contaminated with urine. Historic paintings and photographs were defaced or broken. Other artworks were discovered floating in the water that spread after vandals opened the hydrants.

It was necessary to rescue items amidst the debris and address scratches, dents, ruptures, stains, oxidation, and broken parts, as well as contamination from dry chemical fire extinguishers. Parts of destroyed objects were never recovered. The success of the salvage operation was only possible due to the swift action of the responsible departments, supported by cleaning and maintenance teams, as well as volunteers. However, it was also owed to the management and preservation measures previously implemented.

The importance of inventory

The Senate Museum had just begun cataloguing its collection when the invasions occurred. One of the first areas targeted by the extremists was the exhibition hall, but the inventory of the pieces kept there had already been completed, which made it easier to identify and process the assets to be handled.

In the Chamber of Deputies, the Museum had already inventoried its entire collection. As a result, it had a precise understanding of the quantity, typology, and state of conservation of each item on the inventory list, along with their exact locations within the palace. This information was particularly important due to the frequent movement of artworks requested for the decoration of directorates and parliamentary offices.

Simultaneously, the Preservation Department, in collaboration with other departments responsible for historical and artistic collections, developed and implemented the Preservation Policy, the Risk Management Plan, and the Emergency Preparedness Guide for potential disasters. These efforts, in conjunction with regular training for cleaning and maintenance teams, proved to be indispensable. Within approximately four months, more than 80% of the vandalized items had been processed, cleaned, and/or restored.

Fig. 3. Restorers from the Chamber of Deputies inspect a sculpture by Alfredo Ceschiatti. In the background, a panel by Marianne Peretti. © Pedro França/Agência Senado

Fig. 4. Ostrich Egg, a gift from the President of the National Assembly of the Republic of Sudan to the Chamber of Deputies, before and after the attack. © Câmara dos Deputados/ CEDI/ Seção de Conservação e Restauração

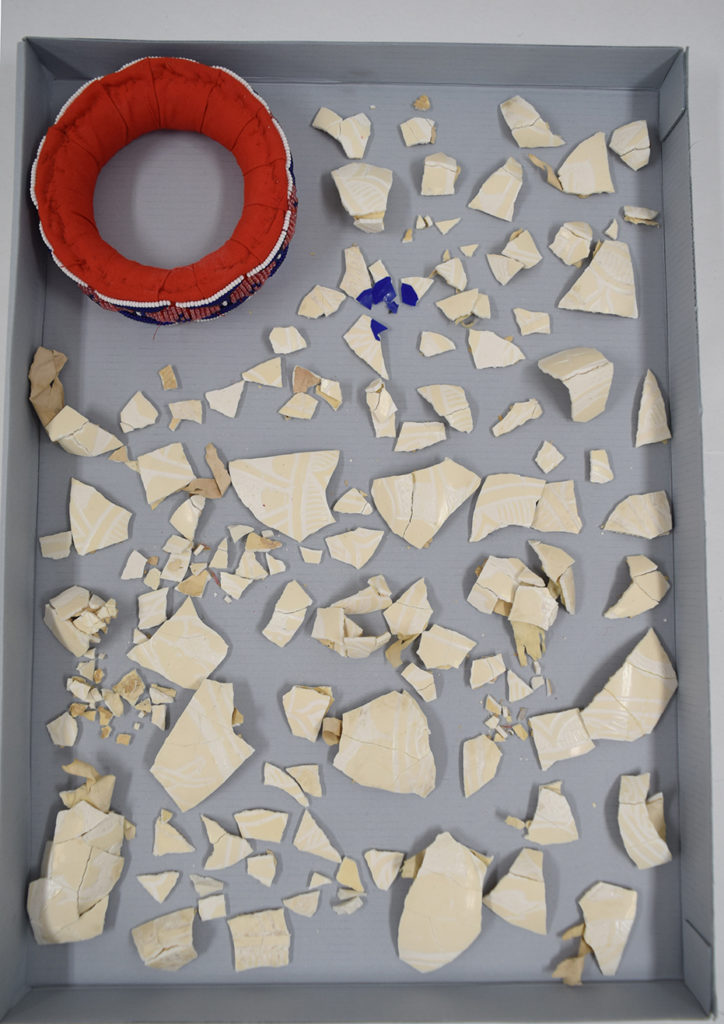

In another line of action, the Supreme Federal Court chose not to restore the original physical integrity of certain assets. With the aim of documenting and re-signifying the events of January 8th, it set up exhibitions featuring damaged objects and other physical remnants from the attack, complemented by photographs of the invasion and the palace’s restoration.

A shared characteristic among some of the institutions previously mentioned is that, in each of them, the awareness of senior management regarding the importance of preserving collections was ignited by the very teams responsible for managing these collections. They often forge strategic external partnerships with authorities and universities, while also successfully engaging a pivotal figure: a project sponsor, a member of the senior administration of the institution, who possesses a substantial degree of influence and authority and can play a role in advocating the project to senior management, therefore enhancing its prospects for approval.

Lastly, it is important to emphasize that Houses such as the Chamber and the Senate, which stand as symbols of Brazilian democracy, must also channel investments into programs that view these collections as instruments for critical reflection and education. Such programs have the potential to bolster society’s historical consciousness and contribute to the establishment of a robust and democratic national identity. Moreover, they might play a role in preventing other acts of vandalism from occurring.

Acknowledgments

This article was made possible primarily through the collaboration of Gilcy Azevedo, former head of the Conservation and Restoration Service, and Ronaldo Carneiro, head of the Conservation and Restoration Section of the Chamber of Deputies; and of Mateus de Carvalho, museologist at the Federal Senate Museum.