This is an extract from the article ‘Mana Taonga and the public sphere: A dialogue between Indigenous practice and Western theory’, originally published on the International Journal of Cultural Studies 2014. In this paper, the authors Philipp Schorch and Arapata Hakiwai discuss Mana Taonga, a cultural policy based on dialogue and negotiation currently in practice at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (Te Papa).

–

Before our National Museum opened in February 1998, it was openly acknowledged that the old museum was not right.

It was a ‘stifling museology’ at its worst where Māori for the most part were the passive observers looking from the outside in. The new National Museum was to be ‘bicultural’ and it had to speak to the uniqueness of our country. Māori clearly did not want a blueprint of the old but instead a museum that recognized and embraced Māori cultural values, tikanga (customs) and knowledge systems.

Te Papa created a structured process of engagement with its communities before it opened and later called it the Mana Taonga principle (see Appendix). Mahuika (1991: 10–11), one of the creators of the Mana Taonga policy, stressed that Māori were poised to see what sort of cultural recognition the new National Museum would get stating that ‘Te Papa is seen by Māori as the first physical demonstration of a bicultural approach to taonga [Māori treasures] and, therefore, a first step towards the recognition of Māori cultural values’ and that ‘through the negotiation process that has typified the museum’s planning, Mana Māori has been transferred and translated into a bicultural expression in the new museum as Mana Taonga’.

Mana Taonga is a key statement and guiding principle for our National Museum and at its core is the recognition that there still exist living relationships and connections between taonga and their cultures of origin. Mana Taonga recognizes that communities have a right to their taonga by virtue of these concrete relationships. It acknowledges the role of communities in the care and management of taonga at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, and their willingness to engage and mediate in new ways. Mana Taonga is central to Māori participation and involvement and in a very tangible way it connects iwi (Māori tribes) to Te Papa via the whakapapa or genealogical relationships of taonga and its knowledge.

“Te Papa is seen by Māori as the first physical demonstration of a bicultural approach to taonga [Māori treasures] and, therefore, a first step towards the recognition of Māori cultural values”

This active process of engagement reflects the connections that exist between the taonga and their makers, kin and descendants. These relationships are often personal and frequently involve kanohi ki te kanohi or a face to face approach. The nature of the relationship can be expressed through such instruments as a memorandum of understanding, a legal agreement or a contract but often they are reinforced with mutual trust and respect for both parties. In all that we do at Te Papa, first we actively seek the support and approval of Māori with respect to the use of any treasure of theirs. This also extends to the interpretation and knowledge base associated with that treasure. Mana Taonga provides great scope for the inclusion of multiple ideas, different voices and competing perspectives, which echoes the hermeneutic complexities of cultural politics which we alluded to in the introduction and ultimately provides richer and more meaningful experiences to visitors. For Te Papa, Mana Taonga is an Indigenous principle that aims to restore the right of Māori to their material culture and thus awards the museum the interpretive authority through its connectivity and meaningful relationships with the communities of origin.

Perhaps the most telling symbolism of Mana Taonga was the transition from the old museum to the new museum in the late 1990s when Māori tribal treasures such as the Te Takinga storehouse and the Te Hau ki Turanga meeting house of Rongowhakaata were carried from the old museum in Buckle Street to the new museum on Wellington’s at Deakin University on Wellington’s waterfront by their tribal descendants. It was a graphic reminder that the new museum vision had started. The concept of Mana Taonga was central in laying the foundation and setting a course for Māori participation and involvement in the Museum of New Zealand when Te Papa first opened in 1998.

Today it still remains a cornerstone of Te Papa’s modus operandi. Broadly speaking the concept recognizes the spiritual and cultural connections of taonga with the people, thus acknowledging the special relationships that these create. Central to Mana Taonga was also the creation of a marae specifically for the new museum. This is significant as adopting the strong Māori cultural institution of a marae also ensured that Māori values and knowledge systems were likewise respected. As Mahuika (1991: 11) noted in the early 1990s:

Te Papa Tongarewa has adopted the Māori perceptions of marae, the meeting house, wharenui, and the courtyard, atea, as part of the new museum. The significance of this acceptance of the concept of marae means that Māori taonga will now have their own cultural environment. This cultural environment will enable people to greet and speak to their taonga.

“For Te Papa, Mana Taonga is an Indigenous principle that aims to restore the right of Māori to their material culture”

Mana Taonga is a policy and principle that recognizes people and cultures. As Healy and Witcomb (2006) argue, Mana Taonga places people at the heart of the museum as a way of focusing on what is important in today’s contemporary world. By doing this, we ensure that the museum remains relevant and connected to its communities. Mana Taonga in essence activates this principle by recognizing that there are real living relationships that exist between the taonga and their descendant source communities. This ensures that cultural recognition, values and knowledge systems are acknowledged. Underpinning the concept of Mana Taonga is the recognition of living cultures and by association the importance of creating meaningful relationships with the communities and peoples from whence the objects and collections originate from and who identify with them. Te Papa’s former Chief Executive, Dr Seddon Bennington (1994: 11), once said that ‘Mana Taonga is not just a way of thinking about the relationship for Māori between objects and their makers. It is also bringing to our consciousness the role and attitude we need to develop in our engagement with other communities’.

–

Philipp Schorch is Head of Research at the State Ethnographic Collections of Saxony, Germany, and Honorary Fellow at the Alfred Deakin Institute for Citizenship and Globalisation, Deakin University, Australia. Philipp received his PhD from the Victoria University of Wellington, Aotearoa New Zealand, and his habilitation from LMU Munich, Germany, and held fellowships at the Lichtenberg-Kolleg – Institute of Advanced Study, Georg-August-University Göttingen, and at LMU Munich (Marie Curie, European Commission). Philipp is co-editor of the volumes Transpacific Americas: Encounters and Engagements between the Americas and the South Pacific (Routledge, 2016) and Curatopia: Museums and the Future of Curatorship (Manchester University Press, 2018)

Dr. Arapata Hakiwai is the Kaihautū or Māori co-leader of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (Te Papa). Arapata Hakiwai belongs to the Ngāti Kahungunu, Rongowhakaata, and Ngāi Tahu tribes and has over 20 years museum experience, including Director, Mātauranga Māori (2003–08), acting CEO in 2014 and Kaihautū (2013-present). He has oversight of the Karanga Aotearoa Repatriation programme at Te Papa and has undertaken the repatriation of Māori and Moriori ancestral remains from museums throughout the world since 2003. Arapata has presented at international conferences, published in academic books and journals, and regularly lectures at Victoria University of Wellington. Dr Hakiwai is also the Commissioner of Culture for New Zealand’s UNESCO Commission.

–

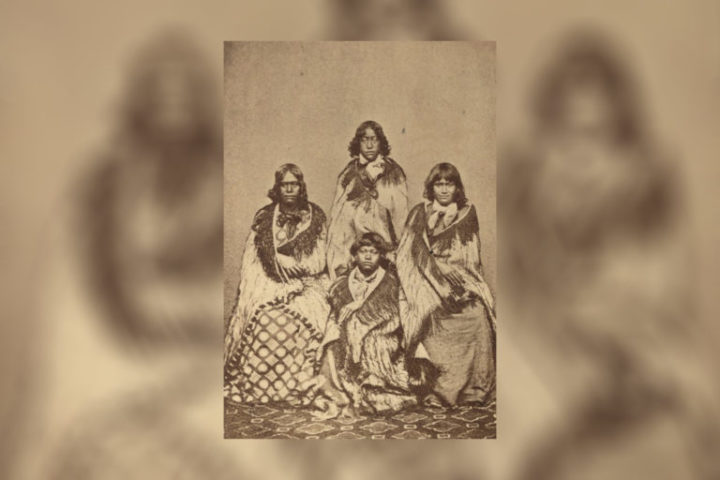

Photo: Four Māori women, c. 1870 – Photothèque du Musée de l’Homme via French National Library (C).