André Delpuech

Director, Musée de l’Homme, Muséum National d’Histoire naturelle, Paris

Museums have no borders,

they have a network

January 19, 2021

Key words: Colonisation; Slavery; Heritage; Archaeology; Monuments; Museums

The list of monuments being taken down has started growing exponentially, with the statue of a slave trader being thrown in the harbour in Bristol, a statue of Leopold II, coloniser of the Belgian Congo, smeared with red paint in Brussels, Christopher Columbus decapitated in Boston, and two statues of abolitionist Victor Schoelcher destroyed in Martinique.

Favouring a Western view of heritage and memory

The figures commemorated by these monuments are linked to the West’s colonial history and the ignominious slave trade and enslavement of Africans. This rise in iconoclasm, sparked by the recent murder of George Floyd in May 2020, is notable in its scale, just like the Black Lives Matter movement. These symbols are under attack because, as they dot the public landscape, they remind descendants of slaves and colonised peoples every day of a painful past and portray an ‘official’ history that is often misleading or biased.

The same can be said for designated heritage sites, which still feature an omnipresent Western architectural vision. Telling examples include sites designated as ‘Historical Monuments’ in the French West Indies. In Guadeloupe, for example, almost all of the 100 monuments classified to date – military buildings, churches and cathedrals, homes and estates, sugar and coffee mills and factories, all striking symbols of colonial power – feature European architecture1. The same can be said for UNESCO World Heritage sites. The 12 listed cultural sites in the Caribbean, for example, are all examples of colonial architecture.2

Honouring new symbols

Local people often have a hard time identifying with such places, which remind them less of the lives of their ancestors than of the power of their masters. But another example from Guadeloupe shows how some are seeking to reclaim their heritage. A military fort in Basse-Terre was long named Saint-Charles and then Richepance, after the general tasked with re-establishing slavery in 1802 following its abolition in 1794 during the revolutionary movement. This was a final insult to the people of Guadeloupe, whose ancestors were reduced to slavery a second time by the general. It was not until 1989 that the monument was renamed Louis Delgrès, after the infantry colonel who led the resistance before sacrificing himself with his troops. This reversal turned a major monument to the power of slaveholders into a symbol of freedom and the fight against servitude.

Making the invisible visible

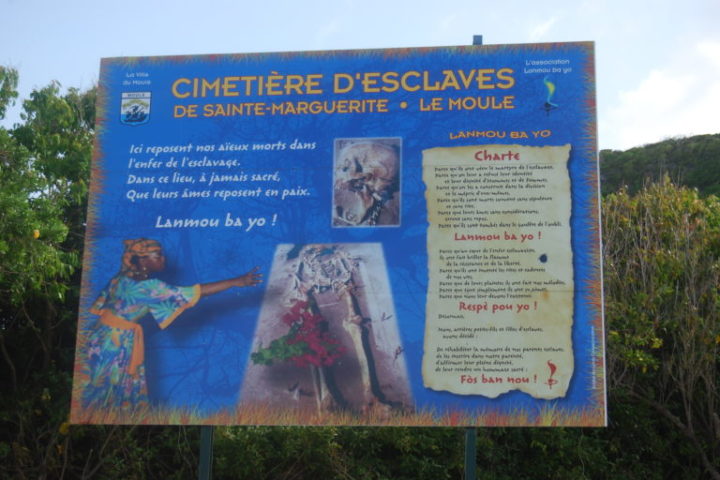

The field of archaeology can create places of memory and reveal remnants of the past that hold identity and even emotion. This ‘archaeology of the discreet’ searches for less spectacular traces of the past – impoverished villages, burial sites, runaway slave camps – left in the ground by enslaved communities. The development of these archaeological digs since the 1990s has allowed African Americans to unearth the legacy of their ancestors, filled with memory and connection3. The best example of this is the slave cemetery at L’Anse Sainte-Marguerite in Guadeloupe. In addition to making a vital contribution to understanding funeral rites and demographics at Caribbean plantations in the 18th century, research turned this deserted space into a memorial that the people of Guadeloupe visit every 27 May to commemorate the abolition of slavery.

In 2019, the Tromelin, the Island of Forgotten Slaves exhibition at the Musée de l’Homme, produced by the Château des Ducs de Bretagne in Nantes, used archaeological research to tell the tragic story of 160 enslaved Malagasies who were abandoned on an island after a shipwreck in the Indian Ocean4. The public success of the exhibition as it travelled to several museums in France showed the interest and the need to reveal this dark side of Western history.

Documenting and exhibiting confiscated memory

However, until recently, the history of slavery and colonisation, the material remnants of those eras, and the creation of contemporary societies born out of the deportation of millions of Africans have been either largely absent from museum collections and discourse or presented in a biased way5.

Fortunately, museums have begun to share these painful histories and show the vitality of the societies that arose from them. Large national institutions have finally opened, like the International Slavery Museum in Liverpool (2007), the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. (2016), and the Mémorial ACTe, or the Caribbean Centre of Expression and Memory of Slavery and the Slave Trade, in Pointe-à-Pitre, Guadeloupe (2015). In the same vein, major museums in France’s Atlantic ports, like the History Museum in Nantes and the Museum of Aquitaine in Bordeaux, have finally begun to discuss their involvement in African slavery and the slave trade. And though we have yet to see a major exhibition on colonial slavery in a notable museum in France’s capital, showing how slavery was a major historic factor in the emergence of modern Europe and contributed to today’s globalised world, we must acknowledge that real progress has indeed been made in the museum world.

It was for these reasons that the renovated Musée de l’Homme wanted its first exhibition in 2017 to serve as a manifesto in the form of Us and Them: From Prejudice to Racism. In another example, in December 2018, to commemorate the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, signed 70 years earlier at the Palais de Chaillot, a season of By Rights! events revisited the articles of this ‘moral horizon of our time’, as it was described by Robert Badinter, beginning with Article 4, which states, ‘No one shall be held in slavery or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms.’ The aim was to also fight the resurgence of such intolerable acts, which are still occurring at the start of this new millennium, where major human rights violations continue to prosper in various forms in many places around the world. For that reason, museums should also do their civic duty in denouncing such acts and protecting freedom.

References and resources

1 Chopin, A. and Plasse, Florent (dir.). 2017. Patrimoine de la Guadeloupe. Paris, Le François: Editions Hervé Chopin, Fondation Clément, p. 607.

2 Sanz, Nuria (ed.). 2005. Caribbean Archaeology and World Heritage Convention. Paris: UNESCO World Heritage Centre, papers 14, p. 210. Special mention must be made of Haiti’s National History Park – Citadel, Sans Souci and Ramiers, a symbol of the first African American Republic.

3 Delpuech, André and Jacob, Jean-Paul (dir.). 2014. Archéologie de l’esclavage colonial. Paris: La Découverte and INRAP, p. 408.

4 Guérout, Max and Romon, Thomas. 2010. Tromelin: l’île aux esclaves oubliés. Paris: INRAP, CNRS Editions, p. 195.

5 Vergès, Françoise (dir.). 2011. Exposer l’esclavage : méthodologies et pratiques. Paris: L’Harmattan, international tribute to Edouard Glissant, 11, 12 and 13 May 2011 at the Musée du quai Branly, p. 224.

_________________

Opinions expressed in the article do not commit ICOM in any way and are the responsibility of its author.