Nick Marchand

Head of International Programmes at the V&A

Museums have no borders,

they have a network

January 17, 2020

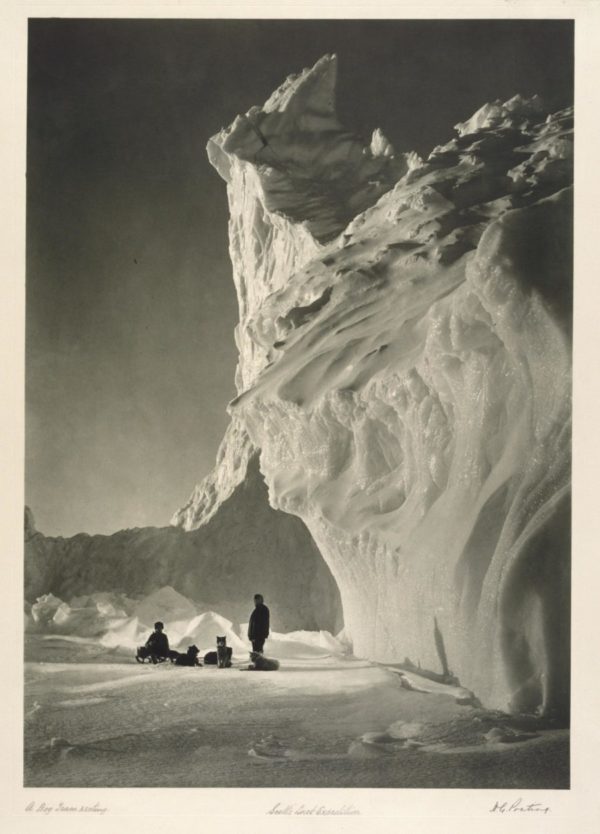

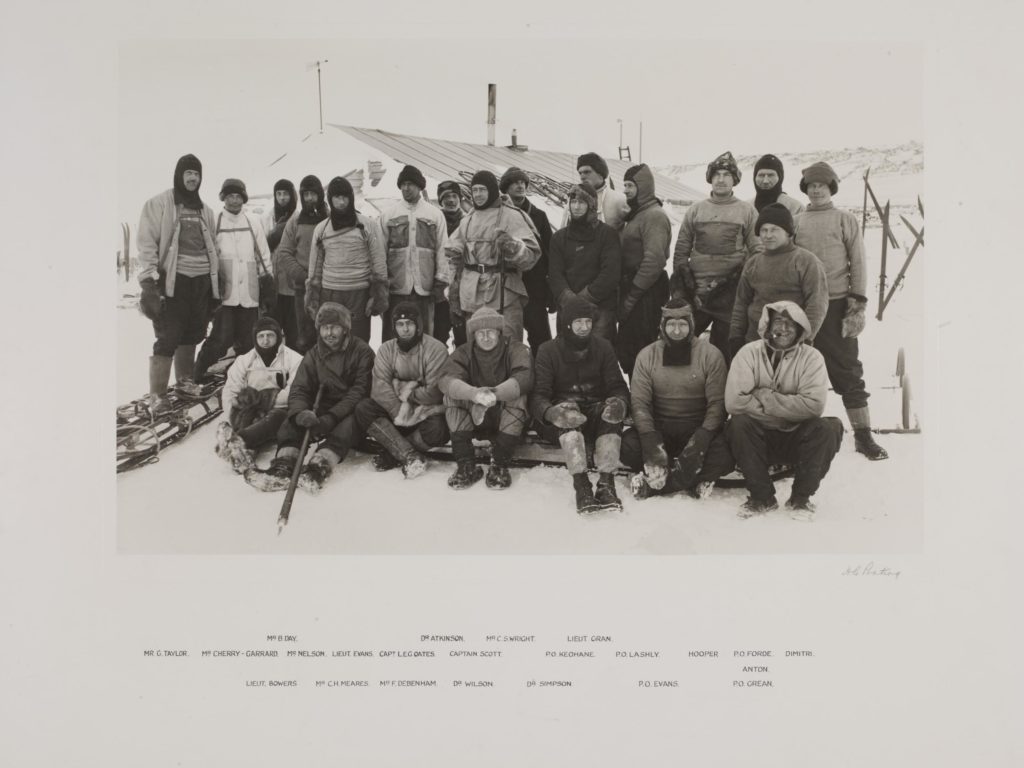

Within the Royal Photographic Society (RPS) Collection, housed here at the V&A, you can see some of Herbert Ponting’s spectacular images of Captain Robert Scott’s last expedition from 1910.

These carbon prints, taken on the foldable quarter plate camera used by Ponting, give an extraordinary sense of the journey they were undertaking. We see Lieutenant Henry Bowers, proud and ready to walk across the ice. There is an iconic image of the dog team resting. A glimpse of the Terra Nova, through a cavern in an iceberg. But of course, looking at these images, it’s hard not to think of Lawrence Oates’ last words to Scott, before he slipped out of their bamboo-framed tent pitched on the Ross Ice Shelf in Antarctica – and stepped into a raging blizzard for the last time…

Now, I appreciate this is not the most cheerful analogy to introduce any museum’s international efforts. However, in my first few months at the V&A, I have been thinking a lot about our museum’s international ambitions. I have also been thinking a lot about what we actually mean by international ambition. The wording, like much wording in a contemporary museum environment, seems loaded with subtext. By its very definition, “ambition” equates to a strong desire for achievement, access, wealth or power. By extension, this achievement comes at a price for someone else.

After Roald Amundsen plunged a Norwegian flag into the ice at “Polheim” – a hastily erected tent at the South Pole – the success of his expedition resonated around the globe. It was different in the UK, of course, where it was Scott’s valiant failure that eclipsed Amundsen’s triumph.

In the last few years, we’ve witnessed some of the world’s great museums establish outposts overseas. For forty years, the Guggenheim’s footprint has expanded, with new adventures in Bilbao, Berlin and Las Vegas, sitting alongside the mooted forays in Helsinki, Guadalajara and Abu Dhabi. We’ve seen the Pompidou in Malaga, Brussels and Shanghai. The Musée du Louvre in Abu Dhabi. The Hermitage in Amsterdam. The Palace Museum to come, in Hong Kong.

These new centres build brand identity, allow increased access to extraordinarily significant collections, stimulate local economies, reach new audiences. Every time one of these new institutions opens, I picture a senior public servant of any one of the other G20 countries (for that’s where they usually come from) rapping their knuckles against a world map and cursing their misfortune to have missed out. The risk of a dropped place in the Soft Power 30. The mounting anxiety around a Ministerial rebuke. Of course, this picture is informed by a history of privilege.

These international stories of daring-do are often measured as wins, quantified as conquests. They are pins on a map to represent the “natural order of things”. One year after the work of Felwine Sarr and Bénédicte Savoy, these stories start to feel like they’ve lost a little of their lustre. Are we simply replaying a cultural variation of the more pugnacious, imperial games played only three or four generations ago? How do we signify best intentions – and are those intentions welcome?

In September this year, V&A Dundee celebrated its first 12 months in operation, having welcomed over 830,000 visitors and contributing £16 million in value to Dundee tourism in 2018. This month, Design Society in Shekou celebrates its second anniversary. A new museum, sitting as part of Sea World Shenzhen, its white tiles gleam against the waters of Shenzhen Bay – as a major new development from China Merchants Group. The V&A is there too. We’ve spent 5 years working with the institution as they build audiences, exhibitions and partnerships for the first major museum in China devoted to design.

So the V&A, just like the Guggenheim, Pompidou, Louvre and Hermitage alongside it, has skin in the game too. But the interesting thing about both V&A Dundee and Design Society, is that the V&A is not the real story. The real story is about the partnerships and environment that completes it.

In Dundee, with the decline of its traditional industry (coincidently, a history that includes the manufacture of RSS Discovery, the ship that took Scott on his first expedition to the Antarctic, and still displayed there today), the city moved to a new plan to reinvent itself as a cultural centre over 30 years. Now founded on the creative industries, traversing arts form and practice, new industry takes up the city’s formerly underused spaces to create a thrilling environment for digital media and the arts.

“The V&A is not the real story. The real story is about the partnerships and environment that completes it.”

Of course, alongside the new environment around it, the success of Scotland’s first design museum is due to the shared efforts and drive of the V&A Dundee team. They have embedded the museum within the cultural fabric of the city – supported by further founding partners including the University of Dundee, Abertay University, Dundee City Council and Scottish Enterprise.

In Shenzhen, we see a city transformed over 40 years, through its status as China’s inaugural Special Economic Zone – leading to the emergence of a new and flourishing design scene. Our partnership is built on a shared conversation driven by a critical moment of creativity and innovation, as Shenzhen pivots from industrial engine to creative capital. As Luisa Mengoni, the former head of the V&A Gallery at Design Society said back in 2016, we are there to “witness a real transition from ‘made’ to ‘created’ in China”. Inspired by that dynamism, we hope to share stories of inspiration and collectively appreciate contemporary feats of ingenuity.

For the V&A, both Dundee and Shenzhen have a directly personal connection. Founded with a mission to educate designers, manufacturers and the public in art and design, our origin lies in the world’s first international display of design and manufacturing – the Great Exhibition. Built on pillars of education and inspiration, the V&A came about at a time of transition, creativity and curiosity. All three echo loudly in Dundee and Shenzhen, offering a genuine, shared framework for engagement.

As conversations continue around ICOM’s alternative museum definition, both the positive and the outraged, the idea of active partnerships contributing to a greater understanding of the world makes sense to me. It champions the idea of a two-way conversation and cultural exchange, together with a more genuine, more nuanced engagement that goes deeper than any financial reward or national standing. To me, that’s an exciting ambition to aim towards.

“The idea of active partnerships contributing to a greater understanding of the world makes sense to me.”

Back on the Ross Ice Shelf – one hundred and six years ago – Scott died just 11 miles short of a food depot, starved of resources, overcome by the environment, and bested by his Norwegian competitor. As the public record states, “The main objective of this expedition is to reach the South Pole, and to secure for the British Empire the honour of this achievement.” Despite a decade of extraordinarily valuable scientific and exploration objectives that came before, Scott was undone by an act of hubris – a race to plant a flag. A salient reminder to us all.

About the author

Nick Marchand is Head of International Programmes for the V&A. Over the last 20 years, he has worked in Australia, China, Hong Kong and the UK. Prior to the V&A, he worked overseas for the British Council, the UK’s international organisation for cultural relations and educational opportunities. He has a background in theatre, as an artistic director, producer and writer.

Main image: Values of Design at V&A Gallery, Design Society © Victoria & Albert Museum, London