Lucía Magnín; Jorgelina Vargas Gariglio

Museum Guide; Research and Fellow Anthropologist at CONICET - Archaeology Department of the Faculty of Natural Sciences and the Museo de La Plata

Museums have no borders,

they have a network

January 26, 2023

Keywords: university museum, guided tours, intercultural educational practice, social museology, indigenous rights.

As museum guides at the Museo de La Plata (MLP), we face great challenges when speaking about the indigenous peoples of Argentina because tense and conflictive situations can arise when interacting with the public. Because of this, as guides, we sometimes avoid in-depth discussions on the issue of the inequalities historically imposed on indigenous peoples.

In this article, we offer two key insights to understand this difficulty in the practice of guiding, that reside in the history of the founding of the MLP and the subsequent relationship between the institution and the indigenous peoples, as well as in the profile of the guides who are part of its educational service today. As guides, with anthropological training and a critical eye, we contribute to consolidating the social role of universities and of university museums.

The MLP was founded in the 19th century as the general museum of the new capital, Buenos Aires, before the creation of the Universidad Nacional de La Plata, on which it later depended in 1906. The collections were the same ones that in 1877 were assembled by Francisco P. Moreno, to constitute the Anthropological and Archaeological Museum of the province. At present, the museum guides are students and graduates of the Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Museo, who work in an area where higher education, university extension courses and museum education meet. As teacher-scientist-extension workers, we bring scientific knowledge closer to the community, whilst also being receivers of other knowledge and perspectives on the different topics we address during guided visits. These topics include the natural history of the region and the cultural diversity of the past and present. To begin the guided tour, the imposing 19th century building offers a journey through its corridors and galleries, a time warp that begins more than 4 billion years ago with the oldest known rocks. It continues through the geological eras, the evolution of living beings and landscapes. Generally, the guides’ main challenge in these galleries is to keep their knowledge up to date with the constant scientific progress in many different areas of knowledge, and to raise awareness of the responsibility we humans have in caring for our planet. However, when we reach the top floor, the anthropological galleries present us with other challenges.

Jorgelina Vargas Gariglio guides a group of scientists attending the 6th National Congress of Argentine Zooarchaeology through the “Espejos Culturales” gallery. © Lucía Magnin.

The Collections that it Pains Us to Present

The gallery “Espejos Culturales” [Cultural Mirrors], exhibits objects, texts and images of indigenous peoples, mostly belonging to the current Republic of Argentina. This museographic ensemble evokes the topic of cultural diversity and also the historically established inequalities imposed on the indigenous peoples. This is a particularly relevant and sensitive subject in our institution, since part of our museum’s collections consist of objects and human skeletal remains belonging to the indigenous peoples who were violently subdued during the territorial consolidation of the Argentinean state in the last decades of the 19th century. “Did indigenous people who were enslaved by science in the 19th century live here?”, or “Is it true that when these people died, their bones were stripped of their flesh and exhibited in the museum’s galleries?”, are just some of the uncomfortable questions we are asked regarding the relationship between the indigenous peoples and those who ran the institution and were in charge of the scientific departments at the time of its foundation. Conversely, our public also has differing opinions on the current policy of not displaying human remains and of returning these remains to the indigenous peoples. On the policy of not displaying human remains, generally they consider the institution’s position to be correct, but they also express interest, or curiosity, in seeing the mummified bodies that were once displayed in the showcases. On the restitution of the human remains, visitors sometimes recall the uncomfortable questions concerning why and how it was that these human remains came to be a part of the collections.

Tensions During Guided Tours

The heritage on display or removed from the exhibition leads us to talk about the current situation of indigenous peoples. While talking to the public, we come across some unscientific but deeply rooted ideas, such as “nowadays there are no real Indians, only their descendants”, or that the cultural origins of our country lie only in the European and white immigrants “who came off the boats”. This questioning of the validity of indigenous identity, or the denial of all things indigenous as part of the cultural heritage of our society, casts doubt on the validity of these peoples’ current claims. From these examples it is possible to sense some of the tensions and emotions arising during the guided tours on the upper floor of the museum.

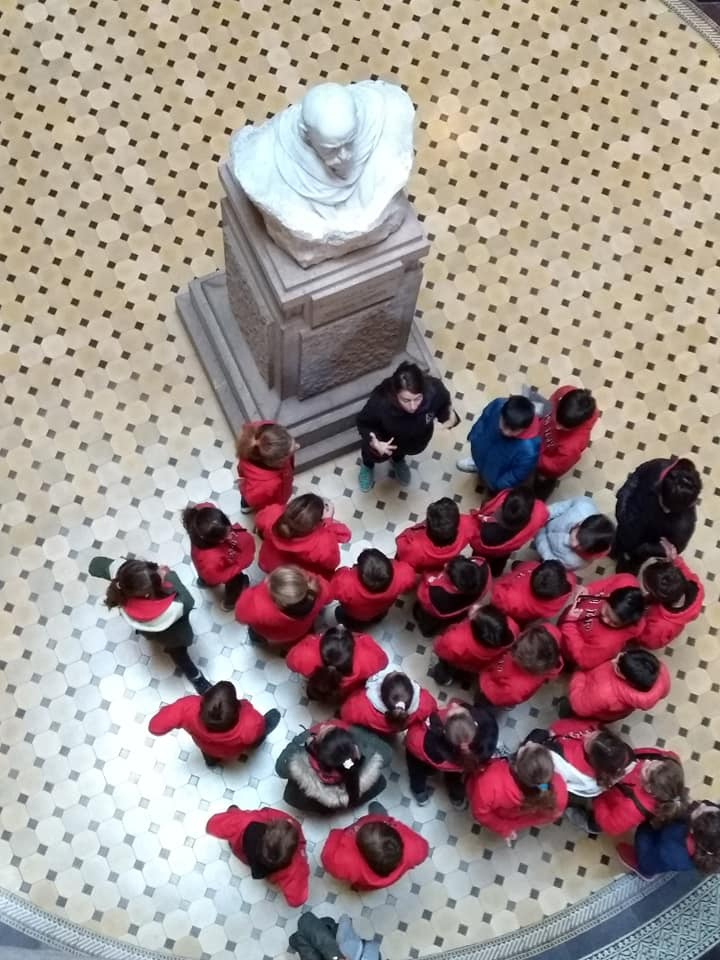

Museum guide, Micaela Medina, welcomes a group of students in the central hall of the Museo de La Plata, next to the bust of its founder, Francisco P. Moreno. © Valeria Aguall

Strategies to Overcome the Difficulties

A contemporary anthropological and critical museological perspective has led us to increase the visibility and recognition of the indigenous peoples of today’s America. The fact that we, as guides, avoid the most emotionally charged situations by evading the issue of the violated rights of the indigenous peoples and the existing claims on the collections kept by the MLP is a problem. Our position as educators is to address these controversial issues in order to be able to engage in dialogue with the public from a current and rights-based perspective.

The MLP is a place for the mobilisation of history, memory, identity and identification with these roots. Its corridors and galleries are spaces that reverberate with the potential to stir up emotions and provide other ways of viewing the world. It is also the place to discuss the very history of how the institution’s first collections were created, which, as in many 19th century science museums, is tainted with practices that treated people as natural, collectible and manipulatable objects.

To capitalise on the “transformative power” of the museum there are many possible courses of action, but, from our position, we propose working as a team to pay greater attention to the stimuli and information that arises during guided tours, such as erroneous and discriminatory ideas as well as ‘fake news’ that circulate in the media concerning indigenous peoples. Our role is essential when interacting with the community, as the inclusion of this topic in the tours depends to a large extent on the mediation undertaken by the guides. Institutional recognition of the team of guides as a community dedicated to thoughtful and professional teaching and learning, capable of identifying problems that are complex to solve, of creating innovations and adopting them effectively, is fundamental to achieve this.

References

Alderoqui, S. y Pedersoli, C. (2011). La educación en los museos: de los objetos a los visitantes. Buenos Aires: Paidós.

Farro, M., 2009. La formación del Museo de La Plata. Coleccionistas, comerciantes, estudiosos y naturalistas viajeros a fines del siglo XIX, Prohistoria. ed. Rosario.

Lanteri, A., 2021. Museo de La Plata. Testimonio del pasado que se proyecta hacia el futuro. La Plata, Buenos Aires: Editorial de la Universidad Nacional de La Plata (EDULP). p. 446.

Reca, M.M. 2017. ‘El museo dialógico “en acción”. Análisis de las representaciones sociales de los visitantes en relación a la exhibición de restos humanos en el Museo de La Plata’. En Museos y visitantes: ensayos sobre estudios de público en Argentina. Ed: M. Bialogorski y M.M. Reca; Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires: ICOM Argentina. pp. 37-68.

Sardi, M; Rodríguez, M. E. 2021. ‘De colección a genealogía: Reflexiones sobre la restitución de Sam Slick; Société Suisse des Américanistes’, Bulletin de la Societe Suisse Des Americanistes, Vol. 81, pp.73-81.

Tamagno, L.E., 2006. Interculturalidad. Una revisión desde y con los pueblos indígenas (Argentina. Diario de Campo 39, suplemento).