I-Yun Cheng

PhD Candidate (Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences) at the University of Sydney

Museums have no borders,

they have a network

March 29, 2024

Introduction

International Mother Language Day is celebrated every year on 21 February. It is a celebration from East Pakistan (currently known as Bangladesh) and West Pakistan (currently known as Pakistan) which aims to highlight the importance of linguistic and cultural diversity all over the world; a theme that is increasingly being addressed. The International Decade of Indigenous Languages (2022-2032), proclaimed by the United Nations, is another initiative that supports this aim, and places even greater emphasis on the conservation and revitalisation of Indigenous languages – especially those that are endangered.

A new national museum dedicated to Indigenous peoples is anticipated to open in Taiwan in 2027. As the majority of Taiwan’s Indigenous languages are in danger of disappearing, it is crucial for current Taiwanese museums dealing with Indigenous heritage to participate in Indigenous language preservation – especially as some of these endangered languages may not be spoken anymore by the time this national Indigenous Museum officially opens.

Taiwanese museums and Indigenous languages

Fortunately, Taiwanese museums and cultural institutions are increasingly participating in efforts to preserve Indigenous languages as a way to safeguard Indigenous cultural heritage in response to the growing global awareness around Indigenous rights and linguistic diversity. According to linguist Robert Blust, Taiwan is considered to be the point of origin of Austronesian languages, which include Taiwanese Indigenous languages, Filipino, Malay, Indonesian, Fijian, Samoan, Tongan, Palauan, Hiri Motu, Māori, Malagasy, and others.

Therefore, preserving Indigenous linguistic diversity in Taiwan is crucial for promoting the linguistic diversity and sustainability of Austronesian languages. Languages are commonly seen as crucial components of ethnic culture from the perspectives of humanities and social sciences. According to the new ICOM museum definition, museums have a crucial role in protecting and interpreting both tangible and intangible heritage to foster diversity and sustainability for the public. Thus, it is essential for Taiwanese museums to focus on preserving Indigenous languages through conservation and interpretation.

As custodians of the cultural heritage of Indigenous native speakers, whether Taiwanese museums have to be responsible for revitalising Indigenous languages has become a debatable issue. Representing only 3% of Taiwan’s population, Indigenous people are usually not very present in museums, both as audience members and curators. Therefore, some non-Indigenous curators might consider that it is unnecessary to provide Indigenous language versions of audio guides and written content on panels, especially for museums with limited budgets and human resources). However, from my perspective, while taking on the responsibility of conserving or retrieving Indigenous languages in museums may make curators’ work more complicated, it is no reason to abandon practicing the linguistic diversity in museums that deal with in Indigenous heritage. Therefore, in the following paragraphs, I will study and compare two exhibitions on Indigenous artefacts in order to analyse the use of Indigenous languages in Taiwanese museums.

Case study 1 : Shung Ye Museum of Formosan Aborigines(順益台灣原住民博物館)

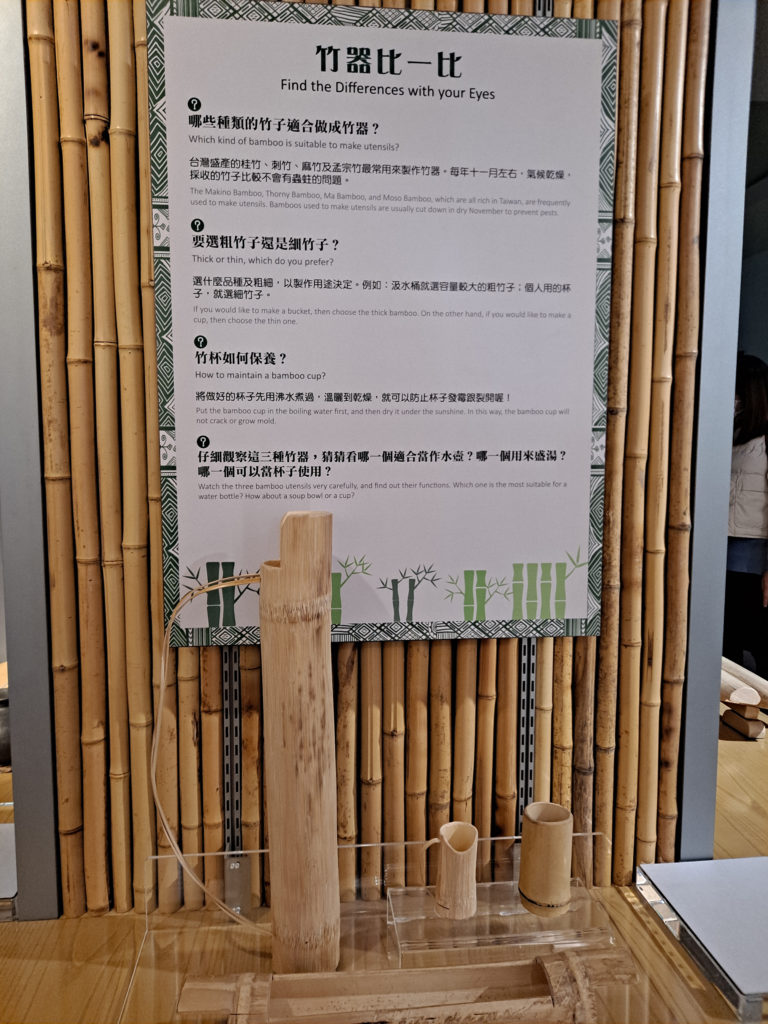

The Shung Ye Museum of Formosan Aborigines was founded on June 9, 1994. Although this museum is a private museum, it contains a wide variety of Taiwanese Indigenous artefacts, even more than many Indigenous cultural institutions supported or operated by the public sector in Taiwan. To support preserving Indigenous cultural heritage, this museum often collaborates with senior Indigenous studies experts or Indigenous communities to curate exhibitions or launch cultural events. However, based on my personal visiting experiences, most of the represented content I explored – in both permanent and temporary exhibitions – was not in Taiwanese Indigenous languages. For example, the panels in the permanent exhibition, which were curated taking into account Taiwanese Indigenous beliefs and rituals, people and natural environment, utensils, dwellings, clothing, decoration and culture, were written in Mandarin and English, and Indigenous languages were excluded. I am not convinced that engaging with Indigenous content is possible without seeing any Indigenous linguistic elements and connections in the exhibitions. While it might be the result of a limited budget, I have to say I felt disappointed because this museum is often seen as one of the most well-known private museums for Indigenous objects in Taiwan. I hope in the future their exhibitions can include and represent Taiwanese Indigenous languages.

Case study 2: The exhibition Lawbubulu: Treasures of Rukai: Homecoming of Century-old Artifacts of the National Taiwan Museum and Wutai Township, from 20/06/2023 to 10/03/2024.

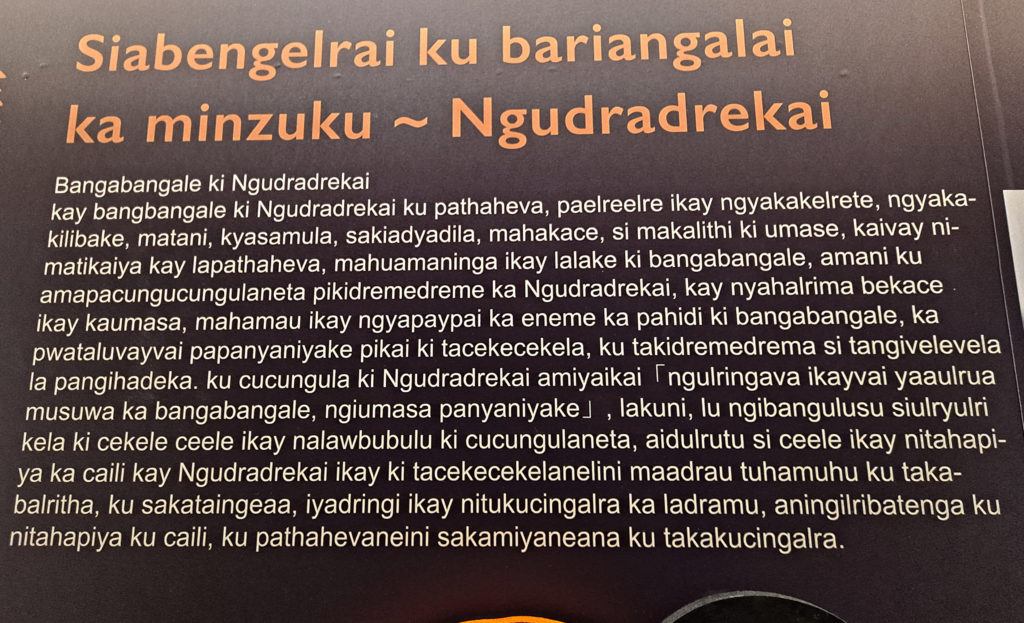

It was not until July 2023 that I visited an Indigenous exhibition curated as I had always hoped. This temporary exhibition featured historical Rukai (one of the Indigenous people of Taiwan) weaving, pottery, sculptures, and knives. According to the museum, some of the displayed items could be traced back to a century ago. On display at the National Taiwan Museum (NTM), the Lawbubulu exhibition featured a total of 150 Rukai artefacts, including 63 objects from the NTM storages, 19 from the Rukai Culture Museum in Wutai Township, 67 on loan from Rukai tribes and 1 carved wooden eave from the Anthropology Museum of National Taiwan University. Although I was delighted to see these incredible artefacts, the exhibition panels were the real highlight of my visit as the curatorial team provided interpretation in Rukai language rather than only in Mandarin and English. Although not all tourists visiting the museum could comprehend the Rukai language, this linguistic representation could more fully embody Rukai culture, which has not evolved into Mandarin or English in Rukai people’s daily lives. This also reminded me of the perspective of Professor Masegeseg Z. Gadu, an influential Indigenous linguist of the Paiwan people and former director of the National Museum of Prehistory of Taiwan: according to him, languages serve not only for communication but also for uncovering the true narrative behind exhibited objects.

Conclusion

Curating an Indigenous exhibition requires knowledge about artefacts. However Indigenous intangible heritage (including oral history, traditional knowledge, etc.) cannot not be understood without speaking the language. Indigenous languages may make an experience more immersive and dynamic by offering interpretive text, audio aids, or knowledgeable guides (who may be Indigenous), just like the in the example of the NTM. Moreover, participating in decolonisation and social justice efforts in museums are current preoccupations in the museum field. It is wrong to continue portraying Indigenous heritages through the lens of colonisers, particularly in museums that house items acquired by colonial measures. Practicing Indigenous linguistic diversity is essential to represent Indigenous heritages and to achieve the goal of cultural sustainability.

References list:

Aborigines, The Shung-Ye Museum of Formosan. ‘Permanent Exhibition’, Accessed 21/10/2023. https://www.museum.org.tw/exhibitions.php?id=3.

Museum, The National Taiwan. 2023. ‘Kialreba Returning Wutai’, The National Taiwan Museum, Accessed 25/02/2024. https://event.culture.tw/mocweb/reg/NTM/Detail.init.ctr?actId=30056&request_locale=en&useLanguage=en.